Three Truths for the Fourth

July 4, 2025

My typical practice for holidays is to ignore them. As a dedicated melancholic, I’m not big on celebrations of any sort.

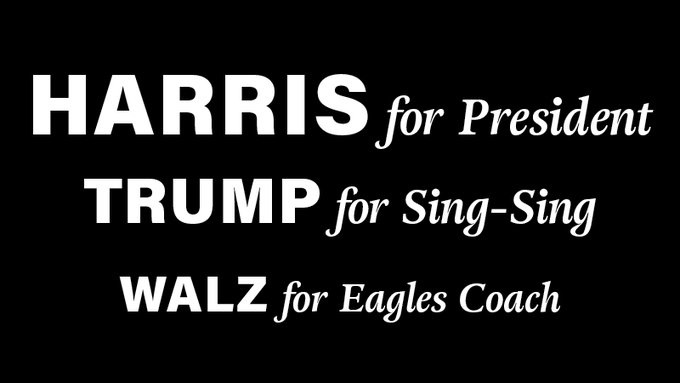

Nevertheless, this Independence Day seems worth marking. It’s the day Trump signs his Big Beautiful Bill to benefit the obscenely wealthy while sentencing millions of low-income Americans to death from lack of medical care. Though the bill is unpopular with the public, the political consequences are uncertain. Thus it’s worth asking why politicians who enact unpopular, even disastrous policies gain power in what is supposed to be a democracy.

I won’t rehash the standard answers to that question: big campaign donors, PACs, gerrymandering, etc. etc. But after the 2024 presidential election, it seemed to me that three fundamental lessons were evident. These lessons are pretty much common knowledge, but they tend to be overlooked by party leaders and pundits who focus on strategic and tactical issues.

Since last November we have been buried in endless, detailed analysis of what Biden did wrong, what mistakes Harris made, and how Trump and his minions played on fears of made-up bogeymen like immigrants and socialists. I’m looking instead at long-term qualities of American society, and American voters, that change very little from one election to the next.

1. Americans are still racist and sexist.

True, in presidential voting, we overcame racism twice with Obama, who was an extraordinary politician with relatively weak opposition; and we beat sexism once when Hillary Clinton took the popular vote in 2016. But conquering both prejudices was simply too much for Kamala Harris, as evidenced by the anecdotes about Black men who thought she was incapable of standing up to Putin. (It probably didn’t help that she’s slim and pretty; if she’d been built like Angela Merkel, she might have been judged more formidable.)

The effects of prejudice on a voter can be quite subtle: a slight, unarticulated reluctance to trust a candidate, or an increased willingness to entertain doubts or slanders. In a campaign full of outrageous lies, this can be enough to change a vote or convince a person to skip voting entirely.

I’m not a pollster, but broadly speaking, I’d say the numbers for Democrats look like this: Nationally, about 45% of votes are automatically lost because of the party label. A Black candidate loses another 3%, a woman 2%. It’s only the undemocratic Electoral College that matters, of course; yet it’s clear that any Democrat other than a white male faces long odds.

Make that a white straight male. We haven’t tested the prejudice against LGBTQ+ folks in a presidential election, but I suspect the numbers are about the same.

Would there be a similar bias against a Jewish candidate? My Jewish wife thinks so. As for a Muslim or Buddhist … let’s not even go there.

This is such a terrible state of affairs that I hope my reasoning is wrong. But we need to face the strong possibility that it’s right.

2. Voters are selfish.

Besides being a truism, this is often considered a positive feature of democracy. I vote for what’s good for me, you vote for what’s good for you, and the overall outcome is what’s best for the majority. But we often fail to realize the supreme dominance of selfishness and the narrow way it functions.

Democrats like myself supported Harris for noble reasons that simply didn’t play with the larger public. For instance, we were taken with grand ideas like these:

a. Preserving democracy against an existential threat. This argument was much too abstract for many voters, even those not attracted by strong-man vibes.

b. Maintaining support for Ukraine. Ukraine is too far away. Europe is too far away. Most American voters may support Ukraine in principle, but at least half don’t fundamentally care.

c. Restraining the genocide in Gaza. Though Biden certainly gave Israel a lot of leeway to kill Palestinian civilians, it was clear that Trump would be even less likely to restrain Israeli hardliners. Yet many voters paid little attention to this issue. Dead Palestinians, so what?

Then what did voters care about? “The price of eggs” became the pop shorthand answer.

Think about how deeply, deeply selfish this is. That’s how people tend to vote.

3. American voters are ignorant.

Many Trump voters were not just ill-informed about the issues and the candidates. They were abysmally ignorant. Things they didn’t know included:

- The foreseeable effect of Trump’s tariffs on inflation, raising “the price of eggs.” Economists kept pointing this out, but Trump voters didn’t hear it or didn’t grasp it.

- The predictable effects of implementing Project 2025, decimating the federal programs that benefit most Americans and undermining the economy for many years to come.

- The likely savagery and economic upheaval of Trump’s plan to deport undocumented immigrants.

Zohran Mamdani, running for mayor of New York, tells of speaking to voters who said they supported Trump because, four years earlier, they had less trouble making ends meet. These people aren’t, by and large, stupid, but they reason in an utterly stupid way; they take hold of one salient idea and block out any qualifiers.

Some of the problem can be attributed to the fragmentation of news sources. I’m old enough to remember the angst of intellectuals when Americans began to gather most of their news from short-form TV programs rather than newspapers and magazines. Yet, from our current perspective, the 1960s and 1970s were far more enlightened. The news shows from the three major networks hewed to a fairly centrist line, and when Walter Cronkite concluded his broadcast by saying, “And that’s the way it is,” he was telling the truth: indeed, that was how it was, more or less, and at the peak of network news, more than 50 million Americans heard it from him or his fellow broadcasters. Now, for large portions of the populace, Walter has been replaced by biased, conspiracy-peddling media pundits.

Many Americans, of course, are willfully ignorant, refusing to attend to any media that don’t confirm their ingrained beliefs. I have to admit that I do not, and will not, watch Fox News, so I remain oblivious to any scrap of truth purveyed by that outlet.

Another reason for mass ignorance may be the decline of civics education in schools. That’s something we might tackle, but oops, the folks in power don’t believe in education, do they?

Whatever the origin, ignorant citizens are a condition we must contend with for years, probably decades, to come. Our leaders will be elected in large part by people who don’t know shit. If you think that sounds elitist, I counter by saying that, yes, it’s elitist and also true.

So these three points, I believe, are fundamental lessons for the Democratic party and any other group that would like to preserve what’s left of our democracy. You have to deal with racism and sexism, appeal to narrow selfish concerns, and overcome colossal ignorance. Among our goodhearted compatriots, who’s ready to tackle such a task?

Political Purity

November 1, 2024

My political voice has been quiet a good while—not calm, just silent. Raging inwardly.

But after hearing about voters casting ballots for third-party candidates, I feel compelled to speak out. Especially to those liberals who plan to vote for Jill Stein instead of Kamala Harris because they can’t tolerate the Biden administration’s support (material if not spiritual) for the Israeli destruction of Gaza. That voting option is terribly wrongheaded, for at least three reasons:

- Yes, the right-wing Israeli government is guilty of, if not genocide, something pretty close to it. But we don’t know that Harris would support Israel as strongly as Biden has. More important, it’s undeniable that Trump would be far worse! (Saying this does NOT indicate that I have the least bit of sympathy for Hamas. In the Mideast conflict there’s enough wrong on all sides for Dante to add another circle of Hell.)

- There ain’t no purity in politics. People who search for an untainted politician might as well wait for the Resurrection. If and when Jesus returns, we can all vote for Him. Until then, we’ll be choosing between greater evils and lesser ones. Shades of gray, always.

- When someone says, “I can’t bring myself to vote for So-and-So,” they are making the election about themselves—that is, about what they need to do to feel moral and upright. Trouble is, the current election is about the whole damn country, maybe the world. It’s not the time to work on self-realization. Let’s be 100% virtuous in our personal lives; volunteer for charity, donate blood, pick up every piece of litter we see. But we must not pretend that such absolutism can help democracy function.

Huhhhhh. (Long exhale. Quiet for a bit now.)

Civil Rights vs. Religion

December 18, 2022

The controversy caused by Lorie Smith, an anti-gay Colorado website designer, has prompted me to think through my position on the issues she raises—issues that pit her religious beliefs against the rights of her (hypothetical) customers. Some of my liberal friends, predictably, have lined up against her. Though I’m way-left on the political spectrum, I don’t find the matter so simple.

To review the situation: Planning to expand her business to include wedding websites, Smith has preemptively sued the state to prevent it from charging her with discrimination if she declines to serve gay couples on account of her religious principles. The U.S. Supreme Court has heard the case and is expected to rule by the end of its current term.

Given Colorado’s actions in the 2018 Masterpiece Cakeshop case, maybe Smith has grounds for worry. In the Masterpiece case, the Colorado Civil Rights Commission ruled against a baker who refused to design a wedding cake for a gay couple, and the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which decided in the baker’s favor.

Of course there’s a large element of political grandstanding in cases like these. They’re based on situations that would never occur in daily life. Any self-respecting gay couple wouldn’t let that baker anywhere near their cake, nor would they let Lorie Smith have a byte of their website.

Still, in spite of the political flapdoodle, cases that pit one person’s rights and moral/religious beliefs against another’s deserve some thought. Imagine a gynecologist who believes that abortion is murder. Would you force her or him to perform an abortion when neither the woman’s nor fetus’s health or welfare demanded it? I wouldn’t, and most Americans probably agree with me on that. Yet if the woman’s life was in danger, the operation had to be done immediately, and no other doctor was available, my opinion would change.

So where do we draw the line? How do we balance the conflicting rights and moralities?

My thinking has coalesced into what could be called a three-pronged test, a term with a nice legal ring to it. Perhaps because they have spiky personalities, judges favor tests with prongs.

Let’s call the parties the Provider and the Customer. Here are the three aspects of the test:

1. The nature of the moral/religious objection. Is the Provider’s disapproval of the Customer based on the latter’s behavior or on unchangeable attributes? It could be that Ms. Smith and some of her right-wing supporters don’t like serving African Americans, but they have enough sense to realize they’d get no sympathy for such a stance, even if they claimed a religious basis for it. People can’t choose their race or skin color. By targeting gays, conservatives are picking a group that engages in behavior they condemn. Yes, LGBTQ folks contend, with reason, that they are born with their gender and sexual preferences, but they don’t have to get married, nor do they even have to have sex. It is, whether we progressives like it or not, a question of their behavior. Passing this behavior test is a precondition for moving on to prongs 2 and 3.

2. The Provider’s degree of involvement with the Customer.

2a. Is the Provider’s involvement passive or active? Jack Phillips, the cakeshop owner, could have no legitimate objection if a gay couple came into his shop and bought a cake from the display case. He probably wouldn’t know they were gay, and even if they identified as such and smooched in front of him, his involvement with them would be minimal: lifting the cake from the case, boxing it, ringing up the sale. In contrast, when they asked him to design a custom cake for them and have it ready on a certain day, they were demanding he take an active role in their wedding, even a “creative” one.

2b. If the involvement is active, to what degree does it involve direct participation in the disapproved behavior? Imagine that Phillips had been asked not just to design and bake the wedding cake in the back room of his shop, but to help cater the event—to come out to the wedding venue, preside over the ceremonial slicing of the cake, and serve the guests? That would be a greater degree of involvement in celebrating an action he considered immoral. An even better example is a wedding photographer who interacts personally and repeatedly with the couple and their relatives and guests.

At step 2a, if the involvement is active rather than passive, I begin to favor the Provider’s point of view, and at 2b I definitely side with him or her. In my daily work, I offer book production services to clients of various backgrounds. If Paul Manafort asked me to edit, design, and print his next memoir, which I suppose should be called A Sleazeball’s Campaign Against Truth and Decency, I’d refuse him on moral grounds. Luckily, sleazeballs are not a protected class, so the law couldn’t compel me.

3. The extent to which the Provider’s service is vital to the Customer’s well-being. I suppose most people take wedding cakes and websites far more seriously than I do. Frankly, I consider them trivial, and my own wedding was the opposite of ceremonial. We didn’t have a cake or website, and we’ve done fine without. Since services like that are not vital—and, besides, are available from multiple vendors—I think the Provider should be free to refuse them even for relatively minor reasons. The opposite would be true of the gynecologist mentioned earlier—the only doctor available when the patient’s life is at stake. In that case, the Customer’s great need should prevail over the Provider’s sense of morality.

Finally, there’s an underlying thought at work here. Most of us get very annoyed when government regulations restrict us personally. We especially hate bureaucrats and their nitpicking, irrational rules. Yet we don’t mind it much when the government restricts others. Let’s keep that in mind. Whatever we think of bigoted bakers and website designers, we should recall that they believe what they believe, and what a government can do to them it might possibly, under other circumstances, do to us.

Bold, Unsupported Predictions

October 5, 2020

Being a person who knows little about politics and misunderstands much of that little, I feel it’s incumbent upon me to share my predictions about the upcoming U.S. election. Clearly the experts are befuddled, so the responsibility for commentary falls on us ignoramuses.

Here’s what I predict:

- President Twitterman will survive the coronavirus. If he suffers mental impairment from the disease, no one will know the difference.

- He’ll lose the popular vote by a large margin (though not nearly as large as he deserves).

- He’ll lose the electoral vote by a frighteningly small margin.

- While making lots of noise about fraud, he will ultimately retire from the fray rather than mount a coup—because, like a typical bully, he’s a coward at heart.

- Though Biden will promise healing, outrage will continue to multiply on both sides, and some people will get killed.

- Ultimately the deplorables, as Hillary Clinton called them, will fade from sight, skulking underground like cicada nymphs until their next chance to emerge. Which they will do, in time.

The Fear Election

July 27, 2020

Reading dozens, maybe hundreds, of articles and surveys and projections about the 2020 presidential election, I’ve been battered by waves of hope, apprehension, suspicion, confusion. It feels like trying to surf in a hurricane.

For better or worse (mostly the latter), I have a simplifying type of mind, the kind that searches for a small number of principles to explain a giant mess. This inclination points me to one basic force behind this year’s politics.

Fear.

The 2020 election will turn, I believe, on what the voters, or those in swing states, are most afraid of.

For some, it’s an amorphous but overriding panic that those people—those who differ from traditional Americans—are taking over the country: i.e., non-whites, non-Christians, non-straights, non-English-speakers, non-male-supremacists, non-rugged-individualists. To liberals, that fear seems so absurd as to be unfathomable, and yet it keeps growing like a poisonous mushroom.

As for the liberals, they (or we, for I’m clearly one) believe the country is on the verge of a fascist dictatorship, even though the president and his cronies have proved massively incompetent at pursuing their agenda. We fear they will intensify the destruction of the rights, and the very lives, of people of color, immigrants, gays, and all other historically marginalized groups (and maybe some new ones they invent). Conversely, we fear their incompetence and stupidity will help the coronavirus kill us all. We can’t decide which is scarier, their actions or their inaction.

1968 was a fear election, at least for Nixon voters, but this year seems even more intense. As anxieties on both sides build, there’s talk—and more fear—of a violent takeover by the other guys, a revolution by the left or a coup from the right. The result is a much fiercer test of our institutions than Nixon ever managed.

George Will just published a column contending that 1942 was just as disruptive as 2020. Perhaps luckily for FDR, that wasn’t a presidential election year. America was hardly unified then, Will points out, even with Hitler and Tojo as looming external threats. “In 1942’s off-year elections, the president’s party took a drubbing.”

Still, this year seems worse in at least one respect: Americans can scarcely agree on a single common enemy. My hero is your enemy—and don’t you dare tear down my statue!

So I wonder, is our democracy, which some say no longer deserves the name, resilient enough to survive, or is it already stretched to the snapping point? I admit to being a sucker for traditional American optimism, but this year, I just don’t know …

Editorial: Twitterman’s Progress

December 28, 2019

According to a news headline today, President Twitterman is breaking from “GOP orthodoxy,” adding a few progressive ideas to his agenda to bolster his chances for reelection. The Gridleyville Editorial Board would like to congratulate him for this evolution in his thought, and specifically for the following new policies he now advocates:

According to a news headline today, President Twitterman is breaking from “GOP orthodoxy,” adding a few progressive ideas to his agenda to bolster his chances for reelection. The Gridleyville Editorial Board would like to congratulate him for this evolution in his thought, and specifically for the following new policies he now advocates:

- Ignoring, like other Republican presidents before him, the GOP mantra of a balanced budget, so that the nation’s deficit will soon set a record at over $1 trillion

- Compromising with Congress on money to Build the Wall, instead of stealing it from military funds

- Increasing air holes in children’s cages along the border, for greater comfort and less suffocation

- Compensating property owners whose drinking water has been contaminated by fracking: at least 1 case of Pepsi per family of 4

- Leniency for those who have witnessed war crimes by the U.S. military: they will not be executed for testifying

If the president continues at this rate, he will soon qualify as an ordinary, corrupt, lobbyist-bought politician, the sort with which we have grown quite comfortable. This is progress indeed.

The True Samaritans

December 22, 2019

During the holiday season, from Thanksgiving through New Year’s, Americans give a lot of lip service to the values of charity, compassion and care for the less fortunate. A few shining exemplars of these virtues are held up by the media, with cheery pictures and sentimental language. Typically, though, we fail to recognize the most charitable of all, the true Samaritans among us.

During the holiday season, from Thanksgiving through New Year’s, Americans give a lot of lip service to the values of charity, compassion and care for the less fortunate. A few shining exemplars of these virtues are held up by the media, with cheery pictures and sentimental language. Typically, though, we fail to recognize the most charitable of all, the true Samaritans among us.

Whom do I mean? Which people are the greatest self-sacrificers?

Actually, they are the people you’d least suspect: the white working- and middle-class straight Americans who support conservative politicians and a right-wing agenda. For short, since their current Great Leader in the White House is President Twitterman, I’ll call them the Lesser Twitters, or LTs.

What’s compassionate about their agenda? you may ask. How can people who favor holding immigrant children in cages be considered Samaritans?

Let’s look at what LTs are giving up and on whose behalf.

Obviously, by supporting policies aimed at benefiting the rich, LTs sacrifice their own prosperity, since the idea that wealth trickles down from top to middle to bottom has been proven a hoax. Nor is it possible that obsolescent, polluting industries like coal mining can ever make a comeback. The “jobs” that right-wing politicians claim to preserve or resurrect will never again be a major force in America. If such activities persist at all in the future, they’ll be done by robots.

On the surface many LTs refuse to accept these truths, but in their hearts they understand, and they realize they are making a sacrifice. They don’t believe, of course, that they are giving up their well-being for the sake of obscenely wealthy corporate leaders, hedge fund managers, and lobbyists. No, in their view they are acting to preserve important social values, such as the right to life and the sanctity of marriage, the issues that Republican politicians have played up for at least two generations, since Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew (both later disgraced and chased from office) began appealing to the “silent majority” in 1969.

What’s interesting is that these so-called family values do not generally affect LTs themselves. If you’re against gay marriage, for example, you won’t marry another person of the same sex, and probably your family members won’t either. Similarly, if you’re against abortion, you don’t have to have one, nor does your partner. These are issues that pertain to other people. By opposing liberal laxity on these matters, LTs are trying to save the rest of us from sin.

Arguably, this is true for even the hottest of hot-button issues, immigration and refugees. Most LTs have scant personal experience with immigrants. Maybe, speeding past in their SUVs, they’ll glimpse a Latino mowing a lawn, or on occasion, through a swinging kitchen door, they’ll catch sight of a swarthy person washing dishes in a restaurant. Hardly a threat in either case. Again, this is a matter that applies to other people, and in screaming their support for cruelty at the border, LTs are acting to save the rest of us who might actually need those jobs mowing lawns or washing dishes, at least until the robots move in.

Let’s take a moment, then, to recognize the LTs as the true Samaritans among us. Yes, they may be rewarded at Armageddon—and at that point they’ll certainly get to shout “I told you so”—but we should offer some appreciation in this life as well.

Let’s each light a holiday candle for the LTs. If you don’t celebrate a holiday involving candles, you can make a cross of two sticks, set it on fire and plant it on a suspicious person’s lawn. It’s the least we can do.

Trampling on Borders: An Apologia

November 29, 2019

My friend Nathaniel Popkin recently published The Year of the Return, an extraordinary novel in which he gives ten separate characters a first-person point of view. They range from young to very old, from a business owner to a truck driver to a journalist to a deeply troubled war vet. To me the undertaking seemed admirably ambitious, and his ability to pull it off impressive. The characters come vividly alive on the page, each with a distinctive voice.

The one technical problem that caused him the most worry? It was not merely technical but social: namely, that he’s white and about half of the characters are black. Here’s what he said in an interview with Mitzi Rapkin for First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing:

Rapkin: Did you have any trepidation at all about writing half the book in the voice of an African-American family, being a white Jewish man?

Popkin: I had terrific trepidation, I still have trepidation. I still worry. I still wonder if it’s the right thing to do or if it’s my privilege or my entitlement to do it. I wonder if it’s right.

As a fiction writer myself, I see two questions here: (1) Can white authors genuinely understand any African American’s perspective or experience? and (2) Even if the authors understand and create believable black characters, do they have any right to publish such work? Is it cultural appropriation?

The first question links to a larger problem for all writers, especially in fiction. Race is only one of many boundaries we have to cross to bring characters to life. Women often have to write about men, and vice versa. Older people write about younger folk, and Millennials take on the Boomers. Same for natives/immigrants. Upper/middle/lower class. Straight/gay/trans. Married/single. War veterans/non-vets.

At a reading once, I heard Elise Juska, who at that point had already published (I believe) three novels, express worry about her novel-in-progress, which required her to imagine the perspectives of older men. My reaction was—I don’t think I said this aloud, but I thought it—that old guys are just like everyone else, only crankier. And any good writer can do cranky. That novel-in-progress became The Blessings, which I consider one of the best American works of fiction of the past decade.

For me, the male-female boundary feels like the easiest one to cross. My male characters too often share my own neuroses, but a woman protagonist is more likely to become her own person. Age is a little harder, class even more so. Occupation often stumps me—when I imagine a character who has a job I don’t know much about, I wonder what that person does all day. The point is that we all have our limitations of experience, and unless we want to restrict ourselves like Jane Austen (who famously avoided male-only scenes because she’d never witnessed one), we need to let imagination carry us past our borders. Bravely or stupidly, we have to venture beyond the comfortable. If the result is a work like The Blessings, the risk will be justified. If we blunder, well, we move on, try something else.

After all, science fiction and historical fiction wouldn’t exist if writers stuck to what they knew. And as Kit de Waal has asked (The Irish Times, 6/30/2018), “Was Gustave Flaubert a woman who committed adultery before he wrote Madame Bovary?”

The second question—the one about cultural or racial appropriation—is trickier. As historically oppressed or undervalued groups raise their own voices, an outsider’s view seems less justified, especially if it comes from a patriarchal, colonial, or privileged background. Kit de Waal, in the article just cited, puts it like this:

So when people who have lost nothing, people from the dominant culture that has colonised half of the world, reigned over an empire, raped, butchered, enslaved, taken language, lands and people as cargo, when those people say there is no such thing as cultural appropriation and insist that we can do what we want, we need to think again of the impact of taking another’s story and using it as we want.

One writer put it this way. Do not dip your pen in somebody else’s blood.

The powers-that-be have told the stories for far too long; it’s time to invert the pyramid. My friend Popkin is a sensitive person who sees many sides of every question, so it’s no wonder he fretted over the matter of entitlement.

But how far should we take this? If we happen to be straight, should we omit LGBTQ characters from our fiction? Should a writer of European heritage shy away from portraying the thoughts and emotions of a Latinx character?

I confess to sinning in these respects, and I don’t think any fiction writer should need to defend the imaginative act of crossing borders, whatever they may be. The resulting work, of course, is ripe for critique. If we stray into new territory and fail to understand it, or leave muddy footprints where they don’t belong, we should get roundly scolded.

Another friend of mine, David Sanders, has published a novel, Busara Road, about a white Quaker kid in Kenya. He himself was once a white Quaker kid in Kenya, so in that respect he was writing what he knew. But for the sake of the novel he also had to create half a dozen major black characters, both old and young, male and female, and that could be considered a violation of boundaries. The result? On a return trip to Kenya, he was told he’d gotten the characters exactly right.

We shouldn’t forget, too, that the insight of an “outsider” can be useful. As Zadie Smith has remarked (The New York Review of Books, 10/24/2019), “For though the other may not know us perfectly or even well, the hard truth is we do not always know ourselves perfectly or well. Indeed, there are things to which subjectivity is blind and which only those on the outside can see.”

To sum up, consider this from Hari Kunzru (The Guardian, 10/1/16):

Good writers transgress without transgressing, in part because they are humble about what they do not know. They treat their own experience of the world as provisional. They do not presume. They respect people, not by leaving them alone in the inviolability of their cultural authenticity, but by becoming involved with them.

Becoming involved with people: after all, that’s what fiction is about.

Democracy and Frogs

June 29, 2019

In my day job, I’ve recently had the pleasure of doing layout on a new translation of an ancient Greek mock-epic poem, “The Battle Between the Frogs and the Mice,” a spoof of heroic war sagas. The new translation by A. E. Stallings, with drawings by Grant Silverstein and an introduction by “A. Nony Mouse,” is due out later this year from Paul Dry Books. The text and illustrations are both gruesome and hilarious.

To summarize the poem’s narrative: After committing a selfish and deadly error, the Frog King concocts lies to evade responsibility, and as part of his cover-up he leads his subjects into a war on false pretenses. Things go badly for the amphibians, and the entire race will be wiped out—until the gods intervene to stave off genocide.

Could there be parallels to the current day?

After pondering this matter, I’ve decided conditions are very different in our democratic era. Because we no longer believe the gods will intervene.

Time to Get Crazy

October 22, 2018

November approaches, and it’s time for one of my periodic screeds about voting. Few things perturb me more than Americans who don’t vote.

November approaches, and it’s time for one of my periodic screeds about voting. Few things perturb me more than Americans who don’t vote.

Well, President Twitterman gets top rank among bugbears, of course. And there’s the Saudi autocrat who’s finally being bashed in the press for murdering one journalist while his mass slaughter of Yemeni civilians continues to be ignored. Yet I don’t know that princely thug called MBS, he’s never bought me a beer, and my outrage at him merges with my general disgust for the fat-cat gangsters swarming the White House and other seats of government.

In comparison, my displeasure with nonvoters is much more personal. You know the truism that sibling feuds are the worst of all? Americans who don’t bother to vote—especially college-educated, middle-class types like myself—those people are family, and so I get really mad at them. There’s no excuse for their behavior. Voting is so simple—how can they not do it?

Do I sound like somebody’s grumpy old uncle?

I am.

Let’s survey some apparent reasons people don’t vote. I’m excusing, of course, those who are blocked from voting by electoral machinations (“you put a period after your middle initial on one form but not on another; therefore we can’t verify your identity”), and those who juggle three jobs and three children and have no time in between, and those whose polling place is conveniently located 153 miles away. Etc. (Although in the latter cases people might use absentee ballots.) I’m aiming this diatribe at people who could vote easily but somehow don’t. The people who elected Twitterman by abstaining. The people who make the United States notorious as a nonparticipative so-called democracy.

Reason for Not Voting #1: “I don’t like any of the candidates. They’re all flawed.”

My response: I hope you believe in a Messiah. Because your perfect political candidate will come along sometime after the Messiah.

Reason for Not Voting #2: “I’m sick of voting for the lesser evil. I can’t compromise like that anymore. From now on, I’ll stand on principle.”

My response: Congratulations on your moral purity. Have you considered moving to a place where none of your principles will be compromised, such as Antarctica?

Reason for Not Voting #3: “None of the candidates talk about issues important to me.”

My response: If you like that situation, keep on not voting. By not expressing your opinion at the polls, you make certain that candidates will disregard it.

Reason for Not Voting #4: “It makes no difference anyway. In my gerrymandered district, people with my views are so outnumbered that my candidate can never win.”

My response: Gerrymandering is a big, big problem. But the canny politicians who divvy up voters for their own advantage are counting on the continuation of established political patterns, including the pattern of people not voting. A sudden swell in ballots from groups they are trying to marginalize could upset their calculations—and maybe set the stage for legislative action to end gerrymandering.

Reason for Not Voting #5: “Votes change nothing. Politicians do whatever nasty things they like regardless of what the public thinks.”

My response: Um, politicians can’t do that nefarious stuff if they’re not in office. Vote them out and they’ll be reduced to making millions as lobbyists. That’s not quite as bad for the rest of us.

I’ve said all this before, in one way or another. But the other day, inspired by a conversation with a politically involved friend, I turned the problem around in my mind, reflecting on what it takes to become a committed voter, someone who turns out in every election:

- A sense of morality or justice. People are said to vote their pocketbooks, and many do, but in our divided times what seems to drive citizens to the polls is a belief that certain actions and policies are right and others are disastrously wrong.

- Faith. Not religious belief necessarily, but a conviction that there’s some hope left for the world and that human actions—our actions—can make a difference. Admittedly, if science says the Earth is likely to be uninhabitable in a few decades, faith stretches thin; but there have been Doomsday scenarios in the past that we managed to escape, and it wasn’t by hiding under our school desks to avert the atomic bomb. We must believe that our flawed and compromised democracy can be salvaged and that its fate is important to the world.

- Irrationality. In the most local of elections, one vote can actually matter. In a 2017 contest Phillip Garcia won the post of judge of election in a Philly precinct because he wrote in his own name—the only vote cast for that office. Still, I have to admit that one vote, which is all each person can control, will change nothing in a statewide or national election. Making a point of casting a ballot is therefore irrational, or at best a stroking of one’s own moral sensibilities (cf. Reason #2 above).

It seems I’ve put myself in the position of urging people to be irrational. Okay, I’ll own up to that. I’ll double down, as Twitterman always does.

Get out there and go crazy, people! Against all reason, act like it makes a difference what you do. Vote for somebody! If necessary, embrace the lesser evil, the best of the bad choices.

Maybe there’s some hidden good there after all.