Historical Delvings

November 7, 2011

When I was an English major, way back before Garrison Keillor started making fun of our tribe, historical fiction was considered minor-league, pop-culture fare, beneath the notice of highbrows in my high-class department. It was OK for Homer, Crane and Tolstoy to set tales in the past—those Great Writers were already in the canon—but in Vietnam-era USA it was incumbent on serious artists to confront the muck and mire of the present day.

When I was an English major, way back before Garrison Keillor started making fun of our tribe, historical fiction was considered minor-league, pop-culture fare, beneath the notice of highbrows in my high-class department. It was OK for Homer, Crane and Tolstoy to set tales in the past—those Great Writers were already in the canon—but in Vietnam-era USA it was incumbent on serious artists to confront the muck and mire of the present day.

Having long left academia behind, I don’t know exactly when that view began to change, but it must now be as archaic as Papa Hemingway’s bullfighters. Doctorow, Eco, Mantel and many others have impressed the critics with fiction set far back from the present time, and today’s readers, whatever their literary pretensions, seem more fascinated with Anne Boleyn’s head than with any contemporary character’s heart.

Cultural anthropologists may want to speculate about why so much modern fiction has taken flight from the modern. Or maybe it’s obvious.

Personally I enjoy good historical novels and always have, even when under the thrall of my snooty English department. Recently I’ve read a couple of fine ones: The Confession of Jack Straw by Simone Zelitch (Black Heron Press, 1991) and The Girl Who Would Speak for the Dead by Paul Elwork (Putnam, 2011; an expanded version of The Tea House, published by Casperian Books in 2007).

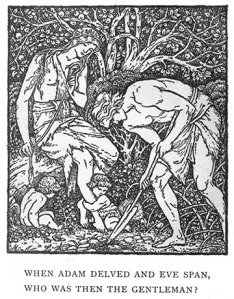

Zelitch recreates the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, when tens of thousands of English folk marched on London to protest an onerous tax (a flat tax—Republicans take note!), a low cap on wages, and other legal shenanigans by which the rich exploited the poor. Professing loyalty to fourteen-year-old King Richard II, the rebels wanted to rid the country of his handlers and advisers, whom they took to be corrupt usurpers of power. Chants of the now-famous rhyme,

When Adam Delved and Eve Span

Who was then the Gentleman?

fostered an idealistic hope that class distinctions might be ameliorated—kind of like our yearning that Wall Street float back down toward Main Street, someday, somehow.

The rebels managed to dispatch several of the supposed usurpers, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, and they torched John of Gaunt’s great Savoy Palace; yet they were eventually betrayed by the teenage king himself. Peasant leaders John Ball, Jack Straw and Wat Tyler were all apparently killed or executed. Straw, the most mythical of the three, was said to have left a “confession,” reproduced in the chronicles of Thomas Walsingham; this dubious document may have been wholly invented—for, as we know all too well, it’s the victors who write the history books.

Zelitch imagines for us the true, undistorted confession of Jack Straw, as dictated to his captors. Her Jack is a conflicted and dynamic figure, compelled to betray either his mentor, the half-crazed preacher John Ball, or his own crippled sister, who needs him back home. Poetic and earnest, full of folk tales and country ale, Jack is a sensuous man who drinks in both the beauty and the stench of his surroundings:

The sun rose to our backs, and we reached Maidstone by late morning. The whole town filled the square to greet us. We had to stop if only to push through the hundred who bore baskets and banners. Two women bore a proud new standard, Adam delving, Eve with spindle. Kate Tyler stood among them, some ways off, and she swung a basket full to overflowing, warm with bread and sour with cheese. Her hair was twisted back, and her face was round and white like a moon or a cheese. (p. 174)

We had to climb many a steep mount of cobbles. Townsmen call them hills. Some streamed stink like waterfalls down clefts you call a gutter. Those guts of rain and dung would overcome the deepest gutter. At odd banks of these hell-rivers the merchants hawked their pies or caps or buckles. (p. 201)

The style—lyrical, evocative, but set in those short chunky sentences like the solid clop of a peasant’s boots—gives the story its unique earthy flavor. This is a strong novel and an impressive feat of recreating the past.

Paul Elwork’s book is also well done, but in his case the historical setting—a country estate on the outskirts of Philadelphia in the 1920s—seems more a convenience than a structural necessity. His principal characters are a twin brother and sister, Emily and Michael, thirteen years old, who pretend they can communicate with spirits. Discovering that she can make an eerie cracking noise with her foot, Emily uses this technique to spook Michael, who at once sees the potential for duping adults in the community. Their con game of “spirit rapping” is loosely based on the real-life saga of the Fox sisters of New York state, who helped spark the spiritualist movement in the mid-1800s. Elwork shifts the story forward to the post–World War I era, when so many have perished in the war and the flu epidemic that the survivors make easy marks for a spiritualist who professes to connect with the dear departed.

Though the details from the 1920s feel authentic, the main interest here is the spiritualism itself—its motivation, its psychological effects, its sometimes tragic consequences. Elwork draws a nice contrast between Emily, who remains dubious about the play-acting, and the cynical Michael, who takes up with a professional con man. Both of these kids seem remarkably adult but believable. And if the harrowing outcome is plotted a bit awkwardly, the tale is a compelling one, drawing out buried family secrets and guilts, recollections and imaginings about the dead, plus a long-suppressed romance. The novel ends by taking advantage of its time frame to skip ahead to 1939, when the world is entering another murderous conflagration. Emily, now a semi-recluse who has studied Dr. Freud in college, reflects on “old things” and on what she has learned or failed to learn. There’s a sense that some passions, dreams, mysteries, misunderstandings—the components of our Freudian underground—are best left unexplored. About her mother’s erstwhile romance, Emily remarks that “as the years went by, I acquired the habit of not asking, and found myself not wanting an answer, despite my occasional curiosity.”

The Bridge-World of Gregory Frost

October 31, 2011

There was a time when I read a lot of science fiction. I think of that period as physical adolescence, as distinguished from the mental adolescence which, as an American male, I have the constitutional right to prolong until my eighties at least.

My physical teens were a long time ago, not quite as far back as Mary Shelley or Jules Verne, but before Dune, before Le Guin. It was the tail end of what’s now considered the golden age of science fiction, dominated by Asimov and Heinlein. Asimov’s Mule became such an unforgettable malignancy that he appeared in my novel The Shame of What We Are.

Today, as a slowly maturing adolescent reader, I value realistic situations, complex characters, and a plot pertinent to current life on earth. These are not the staples of much science fiction or its twin, science fantasy. And yet I dip into the genre now and again, drawn back by the power of the best practitioners to imagine an alternative universe that obliquely and often savagely references our own.

These meditations are prompted by my recent reading of Gregory Frost’s Shadowbridge, the first of a pair of novels positing a world of huge, perhaps endless bridges, one linking to another over a giant sea, with only occasional bits of solid land below. Most of the humans and humanoids live on one span or another and know of other spans only by rumor and legend. Underclasses, barely acknowledged, scrape out a squalid existence in the infrastructure beneath the bridges. Though the spans must have been built by great engineers, their origin is shrouded in creation myths. Social customs and government vary chaotically from span to span. Enigmatic threats abound.

These meditations are prompted by my recent reading of Gregory Frost’s Shadowbridge, the first of a pair of novels positing a world of huge, perhaps endless bridges, one linking to another over a giant sea, with only occasional bits of solid land below. Most of the humans and humanoids live on one span or another and know of other spans only by rumor and legend. Underclasses, barely acknowledged, scrape out a squalid existence in the infrastructure beneath the bridges. Though the spans must have been built by great engineers, their origin is shrouded in creation myths. Social customs and government vary chaotically from span to span. Enigmatic threats abound.

So far, without having read the sequel, Lord Tophet, I can’t say I’m captivated by the characters, who seem strongly bound to archetypes. For my taste, too, the tale dips overmuch into the fantasy side of the genre, with multiple kinds of magic, talking snakes, a malevolent elf, a trickster fox, and an ambient medievalism.

But the image of this bridge-world haunts me, a fascinating nightmare. The cover art doesn’t begin to capture the vivid picture the author conveys. Here’s a description of one of the underworlds:

He lived neither on an island nor on land, nor even upon the water, but within the frame of a span itself. Chiseled supports and struts formed the foundation of the span, beams and cross-ties created an intricate latticework of layers between them. … Few houses beneath the bridge had roofs because there were no elements to protect anyone from—save the prying eyes of those situated above. The thick stalactitic surface of the span provided all necessary protection, and just acquiring the materials to erect walls was hard enough. In most cases divers, who lived on the lower levels, brought up the stone from the sea bottom, especially from around the piers, where the rocky ocean floor had been crushed and heaped as far down as anyone could see. It cost money to pay the divers, and more to have the stones hauled up on ropes and pulleys from layer to layer through the underspan hierarchy. Everyone knew that a stone was going to disappear here and another there as the pile of rock ascended, and if you were lucky and the pullers not too greedy, perhaps half of the original pile made the journey. It was the way of the underspan and no use railing at its unfairness; it had been thus for centuries and would be thus for centuries more. What it meant, however, was that walls were not built very high, but more like boundary markers than sides of a house. Most were not even as tall as the inhabitants themselves. … Privacy was at best an untested notion.

On Halloween night, with ghouls and witches outside, this is scarier, and truer. Gotta try not to dream about it.

Alice Has a Latte

October 20, 2011

Alice Bliss is now in a very cool place, a Philadelphia coffee shop frequented by theater people, schmoozing professionals, young mothers, wide-eyed kids (the cupcakes in the display case are at eye level for a three-year-old), natural-food and buy-local enthusiasts, and occasional salespeople with BlackBerries who wonder why everyone else has a MacBook or iPhone. Alice is waiting on a table for someone to pick her up—in a totally innocent way, of course, since she’s only 15.

Alice Bliss is now in a very cool place, a Philadelphia coffee shop frequented by theater people, schmoozing professionals, young mothers, wide-eyed kids (the cupcakes in the display case are at eye level for a three-year-old), natural-food and buy-local enthusiasts, and occasional salespeople with BlackBerries who wonder why everyone else has a MacBook or iPhone. Alice is waiting on a table for someone to pick her up—in a totally innocent way, of course, since she’s only 15.

For those who are totally mystified: Alice Bliss, by Laura Harrington, is a “travelling book” that I reviewed in my previous post. My copy is now poised to travel along with anyone else who adopts it. It’s a cool novel, with a winning protagonist, so I hope it/she finds a new home soon. The coffee shop staff has been alerted to assist her in her quest.

UPDATE SIX HOURS LATER: She’s gone—eloped with someone else. We hope she’ll send a postcard.

Travels with Alice

October 12, 2011

A Bookcrossing “travelling book” recently came my way: a copy of Laura Harrington’s new novel Alice Bliss. Bookcrossing.com encourages readers to pass along their books, either to acquaintances or to strangers, and then track them to see where they end up. The site supplies tracking numbers along with labels to paste inside a book. Harrington’s publisher, Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, has sent out some prelabeled copies to bloggers to begin the process for Alice Bliss. The idea is to give Alice, a 15-year-old from Massachusetts, a tour of the world. Currently, according to the website, she has reached 30 states and five continents. I suspect my handoff won’t add another state or continent, but I will surely pass the book on.

A Bookcrossing “travelling book” recently came my way: a copy of Laura Harrington’s new novel Alice Bliss. Bookcrossing.com encourages readers to pass along their books, either to acquaintances or to strangers, and then track them to see where they end up. The site supplies tracking numbers along with labels to paste inside a book. Harrington’s publisher, Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, has sent out some prelabeled copies to bloggers to begin the process for Alice Bliss. The idea is to give Alice, a 15-year-old from Massachusetts, a tour of the world. Currently, according to the website, she has reached 30 states and five continents. I suspect my handoff won’t add another state or continent, but I will surely pass the book on.

In a reversal of the typical process, this novel grew out of a musical, Alice Unwrapped, a solo piece that has been performed in New York and Minneapolis. Harrington won a 2008 Kleban Award for the libretto. The tale is a modern-day version of the homefront story—what goes on at home when the men march off to war. And indeed it is the man, Alice’s father Matt, who flies off to Iraq, leaving his wife and two daughters to fend for themselves. They have the support of a grandma, an uncle, and various friends, all of whom prove vital to the family’s well-being.

Somewhat alienated from her mother, teenaged Alice is especially close to her father, who has taught her gardening, baseball, roofing, puttering around a workshop, and other important life skills. Once he’s gone, she wears an old shirt of his every day and insists on planting the garden, by herself, exactly as he would have done it. Her mother worries about Alice’s obsessions but clearly has struggles of her own.

During this stressful time, Alice is also developing feelings about boys, two of them in particular, who provide exciting, ambivalent, and incoherent substitutes for her missing father. Unaccustomed to girl-coming-of-age stories, I found it comforting to discover (if Harrington can be believed) that girls are almost as stupid in their first romances as boys. There are many funny, poignant moments as Alice wavers between the nerd she’s known since childhood and the popular hunk who suddenly notices her.

Though the novel dives deep into Alice’s psyche, Harrington skips on occasion into other points of view, and she does this skillfully enough that I didn’t feel jarred. There are bits seen from the viewpoint of Alice’s mother, her comical Uncle Eddie, and her proto-boyfriend Henry. Although a few of these asides seem unnecessary, they generally add to our understanding of the characters.

The novel’s world, rich as it is, is limited in certain ways: Aside from Eddie, a cool variant of everyone’s disreputable uncle, grown men are scarce in this story. Aside from the war overseas, evil is even scarcer. Everybody is well-meaning. All are trying to make things work. Nobody is inordinately selfish. And yet this world seems true to life—even when everybody means well, suffering happens.

Alice Bliss is an accomplished novel, remarkably so for the author’s first effort in this genre. Though the main audience will surely be female, men won’t be injured by perusing the book, I promise. Maybe men with teenaged daughters will even learn something useful.

The Winters’ Suspense

October 2, 2011

Suspense is just about the oldest trick in fiction. Get the reader on the edge of the seat, demanding to know if the dark figure on the staircase was the villain, if the rescuers will arrive on time, if the assassin will squeeze off his shot—then postpone the revelation till late in the story. Even in literary novels, which presumably have loftier aims than tickling the reader’s thrillbone, prickly suspense is not uncommon. Recently, though, I’ve read a novel that creates suspense at the outset and then downplays it—to the reader’s benefit, I think.

Suspense is just about the oldest trick in fiction. Get the reader on the edge of the seat, demanding to know if the dark figure on the staircase was the villain, if the rescuers will arrive on time, if the assassin will squeeze off his shot—then postpone the revelation till late in the story. Even in literary novels, which presumably have loftier aims than tickling the reader’s thrillbone, prickly suspense is not uncommon. Recently, though, I’ve read a novel that creates suspense at the outset and then downplays it—to the reader’s benefit, I think.

Lisa Tucker’s latest, The Winters in Bloom, begins with the kidnapping of five-year-old Michael, only child of Kyra and David Winter, and both parents quickly and separately assume that their past has come back to haunt them. The suspense is immediate and intense, and we don’t learn the boy’s fate or recognize the kidnapper till the end of the book. You couldn’t ask for a more suspenseful setup.

Nevertheless, early chapters from the boy’s point of view let us know that he’s not in immediate danger, and the author gives us information like this:

“his [the boy’s] assumption that his parents knew this lady would … turn out to be true.… Even his feeling that the lady loved him was true, though her love was a desperate, entirely unexpected response that he couldn’t possibly have made sense of.”

A desperate love—not reassuring, but not likely to lead to murder or abuse, it seems.

The following chapters examine the background of each person in depth, weaving interlocking stories in which the fascination lies not in the plot but in the character development. Though the mystery of the kidnapper’s identity remains strong, the author doesn’t amp up our worry about the boy. The tone is calm, the pace unhurried; it doesn’t feel like the book will end in disaster.

This muting of suspense allows us to pay attention to the characters and to ask, not just who would snatch the boy, but why—what exactly in the past has come back to haunt this family, and how does it make psychological sense? The technique shows a mature author, someone who knows she can hold our interest without sensationalism.

The Winters in Bloom turns out to be a fine novel, both clever and profound, full of subtle characterizations that make sometimes bizarre behavior entirely convincing. I even found myself believing in David, the husband/father of “steady reasonableness” and “cheerful good nature” whose “enormous amount of compassion” leads him time and again to assume the fault is his own. I won’t say whether he proves correct, but on behalf of all husbands I should point out that we aren’t always to blame.

Visiting a Playgroup

September 22, 2011

Recently I’ve been learning about motherhood. Being a father of two and grandfather of five and a half,* I never expected to study mothering except for the few tricks a man needs to know for self-preservation. But reading Elizabeth Mosier’s The Playgroup (part of GemmaMedia’s Open Door series) was entertaining as well as enlightening.

Recently I’ve been learning about motherhood. Being a father of two and grandfather of five and a half,* I never expected to study mothering except for the few tricks a man needs to know for self-preservation. But reading Elizabeth Mosier’s The Playgroup (part of GemmaMedia’s Open Door series) was entertaining as well as enlightening.

The novella (110 pages) focuses on a group of women who have set up a Playgroup ostensibly for their infants, but really to give the mothers a chance to schmooze. And their talk, as Mosier details it, is alternately funny, unsettling, profound, trivial, and full of annoying advice about child-proofing the house. What comes through most strongly is an undercurrent of fear—that a mother will fail at her awesome responsibilities or that this carefully arranged but fragile life will take a gruesome turn. The protagonist, Sarah, pregnant with her second child, has a special dread caused by an abnormality in her sonogram, a small spot “shaped like a cashew.” But uncertainty governs even the most outwardly self-confident of the women:

“Motherhood is like a second adolescence, a time when the self a woman thinks she owns is repossessed by the so-called authorities [all the experts, including family members, who tell her how to be a mother]. She’s left naked and defenseless, asking herself questions about purpose, faith and identity she thought she’d already tamed. … At times, we seemed less like mothers than like insecure teenagers at a beer keg tapping liquid courage, though at Playgroup we swilled coffee while we sought each other’s advice.” (pp. 11–13)

“Loss always lurked beneath our conversations in Playgroup, under talk of microdermabrasion, premenopausal symptoms, IRAs and long-term health insurance.” (p. 72)

The book has one symbolically “perfect” mother, Amy Marley (name reminiscent of Jacob Marley, one of the ghosts in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol), who comes back to haunt the others in an unexpected way, and the arc of her life becomes instructive to all.

During a recent reading at Philadelphia’s Musehouse, the author explained that details of the new mothers’ thoughts and emotional swerves are based on notes she took at that stage of her life. She was brutally honest with herself back then, and her readers get the benefit now.

To give us multiple views of the Playgroup in a short space, Mosier employs a clever narrative device. The first-person narrator, Laurie, begins as a relatively undifferentiated member of the group, and as such she gives us the community outlook on the main character, Sarah:

“Sarah led us into the living room, an arrangement of white chairs and a couch on a white pile rug. … Another group, gathered for a different purpose, might have praised the room’s stark furnishings, but we were there to compare and to judge. Sarah waited nervously for our review.”

Soon, however, Laurie becomes a confidante of Sarah’s, able to reveal Sarah’s thoughts and feelings. Though I was a little less than 100% convinced by this dual narrative function, it should work for 99.9% of readers.

The men in these women’s lives are mostly ignored and irrelevant in the story; they pour margaritas and hammer away at construction projects. Yet the only time I wanted to escape the estrogen-laden environment was when the women started scrapbooking—an activity that, to my relief, the narrator treated with irony.

The book is a quick and fascinating read, and I recommend it to all men who are partnered with a mother, who work with mothers, who stumble upon unfathomable claques of mothers and infants at coffee shops, or who wish to understand why mothers behave in an irrational manner so totally unlike our time-honored male form of irrationality.

*Three dogs, one long-term cat, one short-term cat recently expelled from the immediate family (that’s the half), and one snake. At last count.

Busara Road

September 19, 2011

My friend David Sanders, whom I mentioned in my last post—an excellent writer and all-around good guy—has started a campaign on IndieGoGo.com to support the research for his novel-in-progress, Busara Road. The novel is set in Kenya during the early years after independence—a time when David himself was there, as a child. Now he’s won a prize to help him return to Kenya for a few weeks to work on the novel, meet with leading African writers, and visit the Quaker mission he remembers from childhood.

My friend David Sanders, whom I mentioned in my last post—an excellent writer and all-around good guy—has started a campaign on IndieGoGo.com to support the research for his novel-in-progress, Busara Road. The novel is set in Kenya during the early years after independence—a time when David himself was there, as a child. Now he’s won a prize to help him return to Kenya for a few weeks to work on the novel, meet with leading African writers, and visit the Quaker mission he remembers from childhood.

The great thing about IndieGoGo is that lots of people contribute small amounts to make the project happen. The smallest suggested donation is $10, and you can go even lower than that by clicking on “Other” in the drop-down contribution field. David has listed a variety of creative “perks” for donors, but the main reward is knowing that you gave a little bit to a good artistic cause. So please consider giving the cost of a cappuccino, at least. You’ll be amazed and proud when this novel is published.

Unreliable Narrators

September 16, 2011

On his new blog, David Sanders quotes from J. T. Bushnell’s recent article in Poets & Writers on unreliable narrators. According to Bushnell, even a third-person narrator can be unreliable if the point of view is limited, and he offers this advice:

“you have to know not only who your characters are, but also who they pretend to be, not only what they care about but also what they say they care about, not only what ideas they live by but also how those ideas are false. You have to figure out why your characters are blind, and how they’ve managed to maintain their blindness. And you have to signal these disparities to the reader without revealing them to the character, or straining credibility by making the characters too blind. This creates other dynamics that are necessary in good storytelling, for example, character limitation and unrecognized truth, and moving between the former and the latter helps shape a story’s meaning, or theme.”

I prefer to call a non-personified, third-person narrator a “narrative voice,” and when that voice limits itself to the perspective of a given character, much of what the reader hears can be untrustworthy. However, it’s the character, not the narrative voice, that is unreliable. That’s a trivial distinction, probably—and Bushnell’s summary of what the writer needs to know about each character is certainly a good one.

In a similar vein, Robin Black recently mentioned that the art of writing conversation includes knowing what the people are deliberately not saying. We might add that it also helps to know what the interlocutors are refraining from doing, such as yawning, giving the other person a dope-slap, scratching a devastating itch, and so forth. It’s all in the subtext.

Whipped Cream vs. Hamburgers

September 11, 2011

It’s ten years after 9/11, and are we still postmodern? You’d think a whack of hard reality would have propelled us into a new literary trend, but Paul Auster’s latest, Invisible, which I read because it was lying around my house, remains as metafictional, elusive, shape-shifting, and frustrating as the best/worst of the genre.

It’s ten years after 9/11, and are we still postmodern? You’d think a whack of hard reality would have propelled us into a new literary trend, but Paul Auster’s latest, Invisible, which I read because it was lying around my house, remains as metafictional, elusive, shape-shifting, and frustrating as the best/worst of the genre.

I’m not going to summarize or review the novel, since those tasks have been accomplished so fully elsewhere. You can match a rave from the New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/15/books/review/Martin-t.html

with a pummeling, snarky putdown from The New Yorker

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/books/2009/11/30/091130crbo_books_wood

and end up with the same bemused feeling that I had after finishing the book.

Entertaining as some of Auster’s devices may be, the postmodern conviction that reality is ultimately unknowable doesn’t, in my view, excuse plot turns that are arbitrary and unconvincing or characters who intrigue us into taking an interest but then fizzle out without much development.

This is literary whipped cream. In post-9/11 America, I’d rather have a hamburger.