Historical Delvings

November 7, 2011

When I was an English major, way back before Garrison Keillor started making fun of our tribe, historical fiction was considered minor-league, pop-culture fare, beneath the notice of highbrows in my high-class department. It was OK for Homer, Crane and Tolstoy to set tales in the past—those Great Writers were already in the canon—but in Vietnam-era USA it was incumbent on serious artists to confront the muck and mire of the present day.

When I was an English major, way back before Garrison Keillor started making fun of our tribe, historical fiction was considered minor-league, pop-culture fare, beneath the notice of highbrows in my high-class department. It was OK for Homer, Crane and Tolstoy to set tales in the past—those Great Writers were already in the canon—but in Vietnam-era USA it was incumbent on serious artists to confront the muck and mire of the present day.

Having long left academia behind, I don’t know exactly when that view began to change, but it must now be as archaic as Papa Hemingway’s bullfighters. Doctorow, Eco, Mantel and many others have impressed the critics with fiction set far back from the present time, and today’s readers, whatever their literary pretensions, seem more fascinated with Anne Boleyn’s head than with any contemporary character’s heart.

Cultural anthropologists may want to speculate about why so much modern fiction has taken flight from the modern. Or maybe it’s obvious.

Personally I enjoy good historical novels and always have, even when under the thrall of my snooty English department. Recently I’ve read a couple of fine ones: The Confession of Jack Straw by Simone Zelitch (Black Heron Press, 1991) and The Girl Who Would Speak for the Dead by Paul Elwork (Putnam, 2011; an expanded version of The Tea House, published by Casperian Books in 2007).

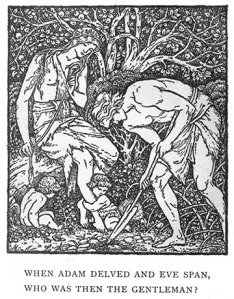

Zelitch recreates the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, when tens of thousands of English folk marched on London to protest an onerous tax (a flat tax—Republicans take note!), a low cap on wages, and other legal shenanigans by which the rich exploited the poor. Professing loyalty to fourteen-year-old King Richard II, the rebels wanted to rid the country of his handlers and advisers, whom they took to be corrupt usurpers of power. Chants of the now-famous rhyme,

When Adam Delved and Eve Span

Who was then the Gentleman?

fostered an idealistic hope that class distinctions might be ameliorated—kind of like our yearning that Wall Street float back down toward Main Street, someday, somehow.

The rebels managed to dispatch several of the supposed usurpers, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, and they torched John of Gaunt’s great Savoy Palace; yet they were eventually betrayed by the teenage king himself. Peasant leaders John Ball, Jack Straw and Wat Tyler were all apparently killed or executed. Straw, the most mythical of the three, was said to have left a “confession,” reproduced in the chronicles of Thomas Walsingham; this dubious document may have been wholly invented—for, as we know all too well, it’s the victors who write the history books.

Zelitch imagines for us the true, undistorted confession of Jack Straw, as dictated to his captors. Her Jack is a conflicted and dynamic figure, compelled to betray either his mentor, the half-crazed preacher John Ball, or his own crippled sister, who needs him back home. Poetic and earnest, full of folk tales and country ale, Jack is a sensuous man who drinks in both the beauty and the stench of his surroundings:

The sun rose to our backs, and we reached Maidstone by late morning. The whole town filled the square to greet us. We had to stop if only to push through the hundred who bore baskets and banners. Two women bore a proud new standard, Adam delving, Eve with spindle. Kate Tyler stood among them, some ways off, and she swung a basket full to overflowing, warm with bread and sour with cheese. Her hair was twisted back, and her face was round and white like a moon or a cheese. (p. 174)

We had to climb many a steep mount of cobbles. Townsmen call them hills. Some streamed stink like waterfalls down clefts you call a gutter. Those guts of rain and dung would overcome the deepest gutter. At odd banks of these hell-rivers the merchants hawked their pies or caps or buckles. (p. 201)

The style—lyrical, evocative, but set in those short chunky sentences like the solid clop of a peasant’s boots—gives the story its unique earthy flavor. This is a strong novel and an impressive feat of recreating the past.

Paul Elwork’s book is also well done, but in his case the historical setting—a country estate on the outskirts of Philadelphia in the 1920s—seems more a convenience than a structural necessity. His principal characters are a twin brother and sister, Emily and Michael, thirteen years old, who pretend they can communicate with spirits. Discovering that she can make an eerie cracking noise with her foot, Emily uses this technique to spook Michael, who at once sees the potential for duping adults in the community. Their con game of “spirit rapping” is loosely based on the real-life saga of the Fox sisters of New York state, who helped spark the spiritualist movement in the mid-1800s. Elwork shifts the story forward to the post–World War I era, when so many have perished in the war and the flu epidemic that the survivors make easy marks for a spiritualist who professes to connect with the dear departed.

Though the details from the 1920s feel authentic, the main interest here is the spiritualism itself—its motivation, its psychological effects, its sometimes tragic consequences. Elwork draws a nice contrast between Emily, who remains dubious about the play-acting, and the cynical Michael, who takes up with a professional con man. Both of these kids seem remarkably adult but believable. And if the harrowing outcome is plotted a bit awkwardly, the tale is a compelling one, drawing out buried family secrets and guilts, recollections and imaginings about the dead, plus a long-suppressed romance. The novel ends by taking advantage of its time frame to skip ahead to 1939, when the world is entering another murderous conflagration. Emily, now a semi-recluse who has studied Dr. Freud in college, reflects on “old things” and on what she has learned or failed to learn. There’s a sense that some passions, dreams, mysteries, misunderstandings—the components of our Freudian underground—are best left unexplored. About her mother’s erstwhile romance, Emily remarks that “as the years went by, I acquired the habit of not asking, and found myself not wanting an answer, despite my occasional curiosity.”