A Fragrant Tragedy

June 10, 2013

From the opening of Ru Freeman’s ambitious and moving new novel, On Sal Mal Lane, set in her native Sri Lanka, we know that tragedy looms. The Prologue, in italics, sketches the background of the conflicts between Sinhalese and Tamils that erupted into war, and the first chapter of regular text begins in this way:

“God was not responsible for what came to pass. People said it was karma, punishment in this life for past sins, fate. People said that no beauty was permitted in the world without some accompanying darkness to balance it out, and, surely, these children were beautiful. But what people said was unimportant; what befell them befell us all.”

Lest we forget the context, this narrative voice from on high returns from time to time to update national political developments and remind us of the doom hanging over the characters.

Yet the novel’s basic action scarcely ventures beyond the tiny, flower-bedecked, semirural lane of the title, on the outskirts of the capital city, Colombo. The people there form a microcosm of Sri Lankan ethnicities and religions—Sinhalese, Tamils, mixed-race Burghers; Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Catholics—all in the space of nine households. Most of the plot centers on the children of Sal Mal Lane, especially the four Herath kids, who are sensitive, talented and a bit more upscale than their neighbors.

Perhaps the novel’s greatest achievement lies in the way it locates significance in the tiniest domestic actions. A wayward teenager, Sonna, quarreling with his father, is denied a birthday party. As a make-do, Sonna’s mother invites the Herath children over for an elaborate dinner without stating that it’s for the boy’s birthday. Later, discovering the truth, the Heraths feel bad that they didn’t take a present. They count out coins from their allowance to buy a chocolate for Sonna, put it in a shiny bag and try to deliver it. He isn’t home, though, so they stash it in their refrigerator to keep it from melting. The next day, Mr. Herath, rummaging for a sweet after lunch, finds the candy and eats it. The children are too abashed to stop him, afraid their mother will find out they’ve been associating with Sonna. Having no money to buy another treat, they reconcile themselves to feeling ashamed, and they let the matter drop.

Ending a chapter, this little tale hovers as a portent. How will the mistakenly consumed chocolate contribute to the slowly unfolding tragedy? This technique encourages the reader to focus on causes rather than on what comes next. For me, though, the weighty foreshadowing has its downside because it discourages page-turning; I was none too eager to arrive at the moment of implosion.

Another potential difficulty is that the profusion of characters makes it hard to become deeply invested in any one of them. Eventually the reader comes to care for several of these people, but it takes a while. Among the Heraths, there are four children of various ages, plus the father and mother. Five other children play significant roles, as do ten or more adults. The interplay is complex, and even the troublemakers and bigots have some redeeming features. The upside is that we get a rich, complex view of a neighborhood, both its uniqueness and its inability to escape the sociopolitical trends that are drawing the larger society into turmoil.

The language is often as fragrant as the blossoming sal mal trees that surround the lane and the spicy curries prepared by the women. In these lyrical passages Freeman’s affection for her homeland shines through. Here’s a paragraph plucked almost at random:

“The gusty wind that dominated a short respite from the monsoons was beginning to tease the children of Sal Mal Lane. It tugged at their school uniforms, inverted umbrellas held against the sun, and combed and recombed their hair, first this way then the other. It whispered stay! stay! to them as they stood waiting for their school buses, shivering in the cool morning hours, a request they tried not to hear. They giggled as their skirts and shirts lifted this way and that, their books fell out of their careless hands, and the ribbons tied into their braids and ponytails, blue and white for the Herath girls, green and white for the Bolling twins, refused to stay in their knots. But each evening the children acquiesced. They put down their books, put on their home clothes, and went outside. They went to fly kites.”

Another treat is the occasional profound remark that could be framed and mounted on the wall. At one point the younger Herath boy, Nihil, seeks reassurance about the rumors of civil war and the announced intention of other boys on the lane to join the army. He questions his friend, old Mr. Niles, who answers: “People do not go to war, Nihil, they carry war inside them.” At times such philosophizing can become a bit heavy-handed, but it serves to reinforce the themes of the novel.

When the long-awaited tragedy arrives, it occurs on two levels. On one level we witness a political event as the quiet street is overcome by the conflict raging around it. But the greater tragedy is rooted in the personal stresses we have seen developing: father vs. son, neighbor vs. neighbor, social outsiders trying to gain a place among those they admire and envy. No one on Sal Mal Lane is entirely innocent. As the second-oldest Herath child, Rashmi, reflects near the end, “Everybody was responsible for what had happened to their street.”

Even as calamity intrudes, however, the people of the lane bond together, across ethnic boundaries. The victims are cared for by their neighbors. The dénouement rekindles a sense of hope, and the novel ends with a young person reading from Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, “a tale of striving for high ideals amid human frailty, turmoil, and change.”

On Sal Mal Lane is not a quick read but one to savor, one whose images and ideas will linger in the reader’s mind.

Tidewater Musings

September 9, 2012

One thing I did while not watching the political conventions was to read a fine book by William Styron, a collection of three long, semiautobiographical stories called A Tidewater Morning. Though I read other major books of his long ago, I have little memory of their details—likely a result of my failings rather than his. Maybe the controversial nature of The Confessions of Nat Turner and Sophie’s Choice overshadowed the actual books, or perhaps it was Meryl Streep in the movie role of Sophie. Or maybe I had to grow sufficiently old and disillusioned to appreciate Styron’s unique blend of realism, strong convictions and subtle romanticism. It also helped that, when I picked up A Tidewater Morning, I had just returned from a Tidewater vacation at a place I affectionately call Mosquitoland USA.

In this collection Styron builds riveting stories on minimal plots. The style mixes the relaxed, leisurely, cultured tone of a Virginia gentleman with postwar explicitness:

Mr. Dabney—at this time, I imagine he was in his forties—was a runty, hyperactive entrepreneur with a sourly intense, purse-lipped, preoccupied air and a sometimes rampaging temper. He also had a ridiculously foul mouth, from which I learned my first dirty words.… His blasphemies and obscenities, far from scaring me, caused me to shiver with their splendor. I practiced his words in secret, deriving from their amalgamated filth what, in a dim pediatric way, I could perceive was erotic inflammation: “Son of a bitch whorehouse bat shit Jesus Christ pisspot asshole!” I would screech into an empty closet, and feel my little ten-year-old pecker rise.

Amalgamated filth—what a phrase! Styron achieves a light, detached irony that doesn’t preclude empathy with his characters. In the story quoted above, “Shadrach,” a superannuated black man trudges from the Deep South with the goal of dying on what is left of the Dabney estate, where he was once a slave. Here is Styron’s description of the reaction by the present Dabney patriarch, whose main line is bootlegging:

Mr. Dabney was by no means an ill-spirited or ungenerous man (despite his runaway temper), but was a soul nonetheless beset by many woes in the dingy threadbare year 1935, being hard pressed not merely for dollars but for dimes and quarters, crushed beneath an elephantine and inebriate wife, along with three generally shiftless sons and two knocked-up daughters, plus two more likely to be so, and living with the abiding threat of revenue agents swooping down to terminate his livelihood and, perhaps, get him sent to the Atlanta penitentiary for five or six years. He needed no more cares or burdens, and now in the hot katydid-shrill hours of summer night I saw him gaze down at the leathery old dying black face with an expression that mingled compassion and bewilderment and stoppered-up rage and desperation, and then whisper to himself: “He wants to die on Dabney ground! Well, kiss my ass, just kiss my ass!”

The way Styron has suddenly returned to my consciousness, I feel a bit of Mr. Dabney’s astonishment.

A Pilgrimage with Hugh Nissenson

June 30, 2012

I hereby publicly confess my sins.… I shall write in plain style and tell the truth as near as I am able.

Such is the promise of Charles Wentworth at the outset of The Pilgrim, Hugh Nissenson’s latest novel (Sourcebooks, 2011), and Charles keeps his word, laying out truths more severely than a fundamentalist preacher. Like Nissenson’s previous works (see, e.g., my comments on My Own Ground), this book makes “unflinching” an understatement. The stern eye on human life will never blink. The Pilgrim is a wise and moving book, a finely crafted book, and not for the faint of spirit.

The year is 1623, and the life of man and woman in Plymouth Colony—and in the England that the colonists have fled—matches the famous phrase Hobbes would use 28 years later in Leviathan: “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Except that Hobbes was describing what he called the state of nature, an imaginary condition without culture or government. Nissenson often turns that philosophy on its head, revealing how much blame lies with the institutions that supposedly protect us from our base instincts.

The demands of his Puritan faith torment Charles; he agonizes over his sins and doubts his salvation. At one point, when he complains to a friend that his soul is “quiescent,” the friend offers the kind of capsule life story that the novel uses several times to devastating effect:

Hook replied, “Better than poor Annie Watts in Worksop. She tormented herself day and night as to whether she be damned or saved. She could not bear not knowing, so she threw her four-month-old babe, Clyde, down a well, wherein he drowned. Said Annie, ‘’Tis better to know that I am damned than not to know what God plans for my soul throughout eternity.’ They hanged her.”

Charles will not fault religion for burdening Annie’s mind or the state for executing a mentally disturbed person, nor will the author breach the form to wink at us. Rather, as the ultimate modernist, Nissenson gives us a narrator who is both reliable in his facts and constricted in his interpretation.

Wherever he roams over space and time, Nissenson immerses himself, and his readers, in the moment. In this novel he wants us to see, hear and smell the 17th-century life of these struggling souls, no matter how gruesome it may be. And there is plenty of gruesome throughout the novel. I’ll forebear quoting from the explicit scenes of hangings, but as forewarning, and as a sample of the masterful way the author assembles simple details, here are a couple of passages:

[A bear baiting in the sin capital of London:]

A bear with little pink eyes pursued one of the mastiffs, while the other five dogs pursued the bear. One dog clung with his jaws to the bear’s left front leg, and the bear bit him through his neck bone and got free. Another dog clung to the bear’s belly, just above his private parts. The bear sat up and, with a front paw, struck the dog’s left shoulder. He would not relinquish his hold. The bear ripped open the dog’s breast with his front claws. I glimpsed the dog’s beating heart. The drunken spectators cheered.[An infected finger:]

The doctor came again and said, “See the thinness of skin about the wound? The abscess is ripe for opening.” He sliced it with his lancet, to a great profusion of blood and pus. The inflammation became livid. Little bladders oozing green and yellow ichors spread all over the skin. The tumor subsided, and for an hour or so, I hoped for the best. Then her whole forefinger turned black.

The “plain style” that Nissenson so skillfully imitates was a deliberate attempt by the Puritans to rid their writing, especially their sermons, of the rhetorical flourishes of the Church of England and the aristocracy. Educated at Cambridge, Charles confesses to being “lewdly disposed to beauteous language,” and in reaction he takes on an almost antiliterary straightforwardness. Even so, the vivid details make his account a compelling read. Here, an ugly scene made me smile because it was so perfectly described:

I alighted from my wagon at the inn named The Sign of the Bear and Ragged Staff in Charing Cross, which is in the City of Westminster, a suburb without the walls of London. The inn was crowded with plump, muddy whores, boy prostitutes, and cutthroats armed with daggers. The press of rowdy maltbugs lugged ale, even as little pigs lug at their dam’s teats.

As that pig indicates, the plain style doesn’t preclude an occasional homely metaphor of the sort that the Puritan preachers loved. Here is Rigdale, a would-be preacher:

“Who is close to Christ all the time? Am I? Surely not. He comes and goes from me like the tide upon the beach I once saw at Dover. At full tide, I am soaked by Him, immersed in His mercy, but then He leaves me high and dry, covered with sandy sea weed. Right now, at this moment, I am high and dry, covered with sea weed, sand, and cockle shells. Yet I have faith that the living waters—His precious blood—will wash over me again.”

And, though less frequent than the horror, there are some genuinely lovely passages, especially when Charles’s faith works well enough for him to appreciate Creation:

On the day following, I went to weed in the cornfield. Just before noon, as I pulled a handful of weeds from the crumbling earth, my eye caught the yellowish tassel protruding atop a red ear of corn from its sheath of pointed leaves. I peeled the leaves back an inch or two. An ant was crawling on one of the red kernels. I gazed at my gloved right hand, holding the weeds with their roots covered with soil, and the shallow hole left in the earth around the stalk. Then I digged beneath the stalk’s roots. There I saw the backbone of a herring [used for fertilizer] that had rotted away.

Then my soul flowed joyfully into those elements of fecundity …

Anyone who has read this far may wonder whether the novel has a plot. It does, concerning Charles’s attempt to find peace with God and himself, and as an adjunct to that quest, a godly woman to support him and ease his lust. Along the way, the reader is treated to Indian wars, the disastrous attempt to establish a new colony, Charles’s family history in England and multiple side stories. The dozens of minor characters include historical ones like Miles Standish, William Brewster, Massasoit and Governor William Bradford. What stands out for me, though, are the stark images of 17th-century life, both outer and inner: the decent man straining to find peace in a human-mucked world with more abominations than beauty—and with ideologies more fanatical than rational.

We’d like to believe our world is vastly different now. Sure it is: we have antibiotics for infected fingers.

The Stockholm Syndrome in Fiction?

May 15, 2012

My alter(ed) ego, as part of his role in hosting a fiction series at Philadelphia’s Musehouse, has been reading new novels by two interesting authors. Liz Moore’s Heft (W. W. Norton) focuses on a housebound ex-professor who weighs more than 500 pounds—a grotesqueness that I thought would put me off. Overall, there are too many characters in contemporary fiction who don’t resemble anyone I know. It turns out, though, that hefty Arthur Opp isn’t grotesque at all, not in ways that count; he’s extremely human and decent and has a fine appreciation for the finer things in life, including but not limited to crab rangoons (“a crunch followed by lush bland creaminess”). He’s a good man whose story of lost love and found friendship grows more fascinating as it proceeds.

Very different but equally entertaining is Marc Schuster’s The Grievers (The Permanent Press), the tale of a prep-school graduate who arranges a memorial event for a classmate who has committed suicide. Marc satirizes every institution in contemporary America from schools to banks to chain restaurants, and his main character, Charley Schwartz, is a smart-ass who never had a good intention he couldn’t undermine with stupid comments. But Charley, like Arthur, grows on the reader, and once he has slashed away everyone’s pretenses, including his own, he finds a way to connect with people at the end.

My alter(ed) ego did an interview with Liz and Marc for the Musehouse blog. You can find it here. They will be reading and schmoozing at Musehouse on May 19 at 7:00.

Among numerous interesting points in the interview, one that jumped out at me was Marc’s comment about the dangers of first-person narration:

The temptation is always there to go into a character’s head and talk about things like guilt and regret. The narrator can do something petty or spiteful, and immediately you can have her turning to the reader with an apology. The real challenge, though, is conveying that kind of information without getting too interior. Ultimately, being in the narrator’s head is a bit like a hostage situation. As a reader, you’re more or less stuck with the character, so it’s only natural to experience a degree of Stockholm syndrome.

The implication that having the narrator express guilt can be the easy way out ties in with my previous post on Jeremy Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending. In that Man Booker–winning novel, Barnes does exactly what Marc worries about, and it bothered me so much that I felt the reverse of the Stockholm syndrome—the narrator’s whining about his guilt distanced me rather than increasing my empathy.

I say this as the author of an entire novel, McAllister’s Fall, predicated on a man’s guilt. In that book, the protagonist semiaccidentally kills a guy with a baseball bat and spends the rest of the novel clumsily trying to make up for his action (and perhaps making things worse in the process). Maybe it’s proper that it remain unpublished so that I can criticize others’ treatment of remorse without suffering the inconvenience of that emotion myself.

The Mystery of Alice and Her Brothers

February 2, 2012

“Henry James was drunk.”

So begins an entertaining literary mystery by Paula Marantz Cohen, What Alice Knew (Sourcebooks, 2010), set in 1888 London during the rampage of Jack the Ripper. Cohen’s animating conceit is that the baffled London police call in the famous American psychologist-philosopher William James for consultation. This puts William in the same city as his brother, the novelist Henry, and their sister Alice, a professional invalid, and the three collaborate in the investigation.

The notion of police employing a psychologist/spiritualist/weirdo is commonplace now, at least in fiction. On TV there’s the popular series The Mentalist, among others. In print, Caleb Carr’s 1994 mystery bestseller, The Alienist, sets up a team of a psychologist, a writer, and a secretary to investigate a serial killer in 1896 New York.

Cohen’s basic set-up is far from original, then. But her Jameses, as eccentric as they are famous, become as psychologically interesting as the killer they track. Alternating their points of view, Cohen allows each to contribute a unique perspective to the investigation. The style is fluid, and the dialogue sparkles. Minor characters like Oscar Wilde and John Singer Sargent step in to enhance the ambiance. Sly humor undercuts the characters’ pretenses, especially Henry’s; the poor chubby aesthete never quite recovers from that classic opening line.

After the recent speculation on the Jameses, Cohen could have made their own relationships as lurid as the Ripper’s slashings. It’s to her credit, I think, that she does NOT put William in bed with Alice, Henry with the male artists’ model, or Alice with her devoted live-in companion. Cohen’s Jameses flout Victorian convention only in their unconventional thinking, which in itself offers plenty of sizzle for this fine novel.

A few announcements to conclude this post:

- The second installment of my story “End of the Ride” is up at The Piker Press. In place of similar annoying advertisements for the third and fourth parts, I’ll direct anyone who’s interested to this link to a page that should list each section as it becomes available.

- My story “MG Repairs,” which came out in Carve Magazine in 2010, will be included in the magazine’s 2009–2010 Anthology. Why two years late? Because editor Matthew Limpede has a sensible approach to the absurd rush of our lives. Myself, I favor setting the clock back to 1993.

- My novel The Shame of What We Are is now available as an e-book from Amazon and Barnes and Noble. Everybody who’s not reading it in paperback can now not read it on a screen as well. But they’ll be missing the wonderful illustrations by Tom Jackson, which come out surprisingly well in the e-book.

- “Wright has found a way to wed fragments of an iconic America to a luminously strange idiom, eerie as a tin whistle, which she uses to evoke the haunted quality of our carnal existence.” So said The New Yorker about poet C. D. Wright, who will be reading on February 2 at Villanova University’s Literary Festival. I love tin whistles. Complete info. about the festival, which will include William Kennedy and several other luminaries, is available here.

Delicate Sensationalism

January 14, 2012

In my disorganized reading of found books—volumes that turn up in the house with no invitation on my part, usually left behind by my wife, daughter, or a friend—the most recent was Black Dogs, a 1992 short novel by Ian McEwan, a writer I admire but can imbibe only in small doses. As is typical of McEwan, the story is unconventional, a bit weird, unpredictable. It’s a good read. Yet it indulges in a technique that my purist side deplores.

In my disorganized reading of found books—volumes that turn up in the house with no invitation on my part, usually left behind by my wife, daughter, or a friend—the most recent was Black Dogs, a 1992 short novel by Ian McEwan, a writer I admire but can imbibe only in small doses. As is typical of McEwan, the story is unconventional, a bit weird, unpredictable. It’s a good read. Yet it indulges in a technique that my purist side deplores.

When pop novelists use bodice-ripping and gruesome slayings to spice up a plot, serious critics can dismiss the effort as mere sensationalism. But what happens when a top-notch literary writer employs similar elements, in a much more skillful way, and presumably to a higher purpose?

In Black Dogs—SPOILER ALERT, if anyone who hasn’t read this 20-year-old novel still plans to—the narrator, Jeremy, is writing a memoir about his in-laws, June and Bernard. The two have long been estranged, in part because of a transforming experience in 1946, on their honeymoon, when June encountered two large dogs in the French countryside. The animals provoked a revelation about good and evil that propelled her into decades of spiritual exploration, at odds with Bernard’s involvement in politics. Tantalizingly, throughout the novel, the author merely alludes to the key event. The explanation arrives in the last chapter with a vivid description of June’s being cornered on a lonely mountain path by feral dogs “of an unnatural size,” as big as donkeys:

she saw them as a juddering accumulation of disjointed details: the alien black gums, slack black lips rimmed by salt, a thread of saliva breaking, the fissures on a tongue that ran to smoothness along its curling edge, a yellow-red eye and eyeball muck spiking the fur, open sores on a foreleg, and, trapped in the V of an open mouth, deep in the hinge of the jaw, a little foam, to which her gaze kept returning. The dogs had brought with them their own cloud of flies. Some of them now defected to her.

The beasts slink forward to attack; June fights them off with rocks, a penknife, a rucksack and a distracting sausage.

But that’s not the real climax.

Later, in the inn where the newlyweds are staying, the proprietress and the mayor explain the dogs’ origin. During the war, the canines were brought to the region by the Nazi Gestapo to terrify the populace, which had supported the Resistance. Left behind when the Germans fled, the dogs have been living off the sheep.

Against the wishes of Mme. Auriac, the innkeeper, the mayor then proceeds with the story of a young woman, Danielle Bertrand, who had moved to the village during the war. She turned up at this very inn one day bleeding and gibbering, with her clothes torn.

Mme. Auriac said quickly, ‘She had been raped by the Gestapo. Excuse me, madame,’ and she placed her hand on June’s.

‘That was what we all thought,” the Maire said.

Mme. Auriac raised her voice. ‘And that was correct.’

‘It’s not what we discovered later. Pierre and Henri Sauvy—’

‘Drunks!’

‘They saw it happen. Excuse me, madame’—to June—‘but they tied Danielle Bertrand over a chair.’

Mme. Auriac slapped the table hard. ‘Hector, I’m saying this to you now. I will not have this story told here.’

But Hector addressed himself to Bernard. ‘It wasn’t the Gestapo who raped her. They used—’

Mme. Auriac was on her feet. ‘You will leave my table now, and never eat or drink here again!’

Hector hesitated, then he shrugged, and he was halfway out of his chair when June asked, ‘They used what? What are you talking about, monsieur?’

The Maire, who had been so anxious to deliver his story, dithered over this direct question. ‘It’s necessary to understand, madame.… The Sauvy brothers saw this with their own eyes, through the window … and we heard later that this also used to happen at the interrogation centers in Lyon and Paris. The truth is, an animal can be trained—’

At last Mme. Auriac exploded.

Though the proprietress goes on to accuse the mayor and his cronies of spreading vicious rumors, the lurid secret is out. The tale is told ever so delicately, with many hesitations by the characters themselves, the culminating words never actually spoken … but it’s sensational nonetheless, and in this moment the titular black dogs acquire their full load of symbolism for June and for the reader.

And at this point in the book, a dozen pages from the end, I was annoyed at McEwan.

Not that I mind hearing about monstrous things in fiction. But there’s a tawdriness in this teasing and titillating of the reader to build toward a revelation of appalling sexual torture. It doesn’t matter how fine the prose—which indeed is brilliant—and it doesn’t matter whether rape by trained dogs was in fact a Nazi method. Nor does the symbolic intention justify this device. The author is playing with the reader’s ability (and willingness) to be shocked, and in my snooty opinion that’s a low-class trick unworthy of the best fiction.

All right, I admit it: in literary terms, I’m a prig.

Now I’ll move on to the next found book, which an unidentified person just slipped through our mail slot: the peculiarly appropriate Dogs for Dummies—a donation inspired, no doubt, by our new terrorist puppy.

Historical Delvings

November 7, 2011

When I was an English major, way back before Garrison Keillor started making fun of our tribe, historical fiction was considered minor-league, pop-culture fare, beneath the notice of highbrows in my high-class department. It was OK for Homer, Crane and Tolstoy to set tales in the past—those Great Writers were already in the canon—but in Vietnam-era USA it was incumbent on serious artists to confront the muck and mire of the present day.

When I was an English major, way back before Garrison Keillor started making fun of our tribe, historical fiction was considered minor-league, pop-culture fare, beneath the notice of highbrows in my high-class department. It was OK for Homer, Crane and Tolstoy to set tales in the past—those Great Writers were already in the canon—but in Vietnam-era USA it was incumbent on serious artists to confront the muck and mire of the present day.

Having long left academia behind, I don’t know exactly when that view began to change, but it must now be as archaic as Papa Hemingway’s bullfighters. Doctorow, Eco, Mantel and many others have impressed the critics with fiction set far back from the present time, and today’s readers, whatever their literary pretensions, seem more fascinated with Anne Boleyn’s head than with any contemporary character’s heart.

Cultural anthropologists may want to speculate about why so much modern fiction has taken flight from the modern. Or maybe it’s obvious.

Personally I enjoy good historical novels and always have, even when under the thrall of my snooty English department. Recently I’ve read a couple of fine ones: The Confession of Jack Straw by Simone Zelitch (Black Heron Press, 1991) and The Girl Who Would Speak for the Dead by Paul Elwork (Putnam, 2011; an expanded version of The Tea House, published by Casperian Books in 2007).

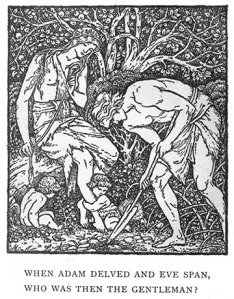

Zelitch recreates the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, when tens of thousands of English folk marched on London to protest an onerous tax (a flat tax—Republicans take note!), a low cap on wages, and other legal shenanigans by which the rich exploited the poor. Professing loyalty to fourteen-year-old King Richard II, the rebels wanted to rid the country of his handlers and advisers, whom they took to be corrupt usurpers of power. Chants of the now-famous rhyme,

When Adam Delved and Eve Span

Who was then the Gentleman?

fostered an idealistic hope that class distinctions might be ameliorated—kind of like our yearning that Wall Street float back down toward Main Street, someday, somehow.

The rebels managed to dispatch several of the supposed usurpers, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, and they torched John of Gaunt’s great Savoy Palace; yet they were eventually betrayed by the teenage king himself. Peasant leaders John Ball, Jack Straw and Wat Tyler were all apparently killed or executed. Straw, the most mythical of the three, was said to have left a “confession,” reproduced in the chronicles of Thomas Walsingham; this dubious document may have been wholly invented—for, as we know all too well, it’s the victors who write the history books.

Zelitch imagines for us the true, undistorted confession of Jack Straw, as dictated to his captors. Her Jack is a conflicted and dynamic figure, compelled to betray either his mentor, the half-crazed preacher John Ball, or his own crippled sister, who needs him back home. Poetic and earnest, full of folk tales and country ale, Jack is a sensuous man who drinks in both the beauty and the stench of his surroundings:

The sun rose to our backs, and we reached Maidstone by late morning. The whole town filled the square to greet us. We had to stop if only to push through the hundred who bore baskets and banners. Two women bore a proud new standard, Adam delving, Eve with spindle. Kate Tyler stood among them, some ways off, and she swung a basket full to overflowing, warm with bread and sour with cheese. Her hair was twisted back, and her face was round and white like a moon or a cheese. (p. 174)

We had to climb many a steep mount of cobbles. Townsmen call them hills. Some streamed stink like waterfalls down clefts you call a gutter. Those guts of rain and dung would overcome the deepest gutter. At odd banks of these hell-rivers the merchants hawked their pies or caps or buckles. (p. 201)

The style—lyrical, evocative, but set in those short chunky sentences like the solid clop of a peasant’s boots—gives the story its unique earthy flavor. This is a strong novel and an impressive feat of recreating the past.

Paul Elwork’s book is also well done, but in his case the historical setting—a country estate on the outskirts of Philadelphia in the 1920s—seems more a convenience than a structural necessity. His principal characters are a twin brother and sister, Emily and Michael, thirteen years old, who pretend they can communicate with spirits. Discovering that she can make an eerie cracking noise with her foot, Emily uses this technique to spook Michael, who at once sees the potential for duping adults in the community. Their con game of “spirit rapping” is loosely based on the real-life saga of the Fox sisters of New York state, who helped spark the spiritualist movement in the mid-1800s. Elwork shifts the story forward to the post–World War I era, when so many have perished in the war and the flu epidemic that the survivors make easy marks for a spiritualist who professes to connect with the dear departed.

Though the details from the 1920s feel authentic, the main interest here is the spiritualism itself—its motivation, its psychological effects, its sometimes tragic consequences. Elwork draws a nice contrast between Emily, who remains dubious about the play-acting, and the cynical Michael, who takes up with a professional con man. Both of these kids seem remarkably adult but believable. And if the harrowing outcome is plotted a bit awkwardly, the tale is a compelling one, drawing out buried family secrets and guilts, recollections and imaginings about the dead, plus a long-suppressed romance. The novel ends by taking advantage of its time frame to skip ahead to 1939, when the world is entering another murderous conflagration. Emily, now a semi-recluse who has studied Dr. Freud in college, reflects on “old things” and on what she has learned or failed to learn. There’s a sense that some passions, dreams, mysteries, misunderstandings—the components of our Freudian underground—are best left unexplored. About her mother’s erstwhile romance, Emily remarks that “as the years went by, I acquired the habit of not asking, and found myself not wanting an answer, despite my occasional curiosity.”

The Bridge-World of Gregory Frost

October 31, 2011

There was a time when I read a lot of science fiction. I think of that period as physical adolescence, as distinguished from the mental adolescence which, as an American male, I have the constitutional right to prolong until my eighties at least.

My physical teens were a long time ago, not quite as far back as Mary Shelley or Jules Verne, but before Dune, before Le Guin. It was the tail end of what’s now considered the golden age of science fiction, dominated by Asimov and Heinlein. Asimov’s Mule became such an unforgettable malignancy that he appeared in my novel The Shame of What We Are.

Today, as a slowly maturing adolescent reader, I value realistic situations, complex characters, and a plot pertinent to current life on earth. These are not the staples of much science fiction or its twin, science fantasy. And yet I dip into the genre now and again, drawn back by the power of the best practitioners to imagine an alternative universe that obliquely and often savagely references our own.

These meditations are prompted by my recent reading of Gregory Frost’s Shadowbridge, the first of a pair of novels positing a world of huge, perhaps endless bridges, one linking to another over a giant sea, with only occasional bits of solid land below. Most of the humans and humanoids live on one span or another and know of other spans only by rumor and legend. Underclasses, barely acknowledged, scrape out a squalid existence in the infrastructure beneath the bridges. Though the spans must have been built by great engineers, their origin is shrouded in creation myths. Social customs and government vary chaotically from span to span. Enigmatic threats abound.

These meditations are prompted by my recent reading of Gregory Frost’s Shadowbridge, the first of a pair of novels positing a world of huge, perhaps endless bridges, one linking to another over a giant sea, with only occasional bits of solid land below. Most of the humans and humanoids live on one span or another and know of other spans only by rumor and legend. Underclasses, barely acknowledged, scrape out a squalid existence in the infrastructure beneath the bridges. Though the spans must have been built by great engineers, their origin is shrouded in creation myths. Social customs and government vary chaotically from span to span. Enigmatic threats abound.

So far, without having read the sequel, Lord Tophet, I can’t say I’m captivated by the characters, who seem strongly bound to archetypes. For my taste, too, the tale dips overmuch into the fantasy side of the genre, with multiple kinds of magic, talking snakes, a malevolent elf, a trickster fox, and an ambient medievalism.

But the image of this bridge-world haunts me, a fascinating nightmare. The cover art doesn’t begin to capture the vivid picture the author conveys. Here’s a description of one of the underworlds:

He lived neither on an island nor on land, nor even upon the water, but within the frame of a span itself. Chiseled supports and struts formed the foundation of the span, beams and cross-ties created an intricate latticework of layers between them. … Few houses beneath the bridge had roofs because there were no elements to protect anyone from—save the prying eyes of those situated above. The thick stalactitic surface of the span provided all necessary protection, and just acquiring the materials to erect walls was hard enough. In most cases divers, who lived on the lower levels, brought up the stone from the sea bottom, especially from around the piers, where the rocky ocean floor had been crushed and heaped as far down as anyone could see. It cost money to pay the divers, and more to have the stones hauled up on ropes and pulleys from layer to layer through the underspan hierarchy. Everyone knew that a stone was going to disappear here and another there as the pile of rock ascended, and if you were lucky and the pullers not too greedy, perhaps half of the original pile made the journey. It was the way of the underspan and no use railing at its unfairness; it had been thus for centuries and would be thus for centuries more. What it meant, however, was that walls were not built very high, but more like boundary markers than sides of a house. Most were not even as tall as the inhabitants themselves. … Privacy was at best an untested notion.

On Halloween night, with ghouls and witches outside, this is scarier, and truer. Gotta try not to dream about it.

Alice Has a Latte

October 20, 2011

Alice Bliss is now in a very cool place, a Philadelphia coffee shop frequented by theater people, schmoozing professionals, young mothers, wide-eyed kids (the cupcakes in the display case are at eye level for a three-year-old), natural-food and buy-local enthusiasts, and occasional salespeople with BlackBerries who wonder why everyone else has a MacBook or iPhone. Alice is waiting on a table for someone to pick her up—in a totally innocent way, of course, since she’s only 15.

Alice Bliss is now in a very cool place, a Philadelphia coffee shop frequented by theater people, schmoozing professionals, young mothers, wide-eyed kids (the cupcakes in the display case are at eye level for a three-year-old), natural-food and buy-local enthusiasts, and occasional salespeople with BlackBerries who wonder why everyone else has a MacBook or iPhone. Alice is waiting on a table for someone to pick her up—in a totally innocent way, of course, since she’s only 15.

For those who are totally mystified: Alice Bliss, by Laura Harrington, is a “travelling book” that I reviewed in my previous post. My copy is now poised to travel along with anyone else who adopts it. It’s a cool novel, with a winning protagonist, so I hope it/she finds a new home soon. The coffee shop staff has been alerted to assist her in her quest.

UPDATE SIX HOURS LATER: She’s gone—eloped with someone else. We hope she’ll send a postcard.