How Rumpy Surprised Me

September 20, 2025

Liberal types like Yours Truly thought we knew how bad the Big Rump would be when he reclaimed his throne and won control of Congress as well. We knew about Project 2025, and we saw in the latter stages of his first residency that he’d figured out the value of filling key offices with little rumpies (lackeys) who’d do anything he told them. We knew he’d cripple the economy with tariffs, undermine Ukraine, and give Bibi the Nutty Yahoo free rein to kill Palestinians. We guessed that, along the way, he’d enrich himself, his family, his cronies. So we went around muttering darkly about the end of democracy at home and looming disasters abroad; we stared at the sky to find signs it might fall.

But I for one should admit that, so far, it’s been worse than expected. He’s surprised me in a number of ways.

First, his whimsicality and general incompetence haven’t hindered him as much as I presumed, partly because the little rumpies he’s appointed have been so zealous in their destruction of norms and institutions. They too are often incompetent, but their angry persistence helps break through commonsense resistance. I certainly didn’t anticipate that he’d empower a MuskRat to gut scores of government agencies.

Second, he has weaponized Big Gov more than I realized possible. I mean, all those agencies, some of which I’d never heard of, cracking down on everybody? Pulling funding, for one thing, and using threats to pressure even megacorps and major universities? Who knew he could get a comedian fired from a huge broadcast network simply by demanding it?

Third, I didn’t anticipate the abundance of CorCows and UniCows—corporations and universities proving themselves abject cowards when faced with the possibility that he’d block their oligarchic mergers or attack their funding. I would have expected an ounce of self-respect from the leaders, boards, and trustees of these institutions. I was so naïve!

Fourth, his ability simply to break the law without consequences—and often ignore court rulings—has gone beyond my predictions. It’s not just raping the occasional female or scamming the public or committing bribery. It’s deporting immigrants despite a court’s telling him not to, blowing up boats in international waters, sending troops to bully cities with fake claims of an emergency. Granted, he seems to have pulled back lately on outright defiance of court orders, but maybe that’s from confidence that his Supreme cronies will ultimately rule in his favor.

Fifth, I didn’t guess how blatantly out in the open all this would be. Yes, his agencies have banged the shutters against transparency. But in the broadest sense, we’ve seen self-dealing with no sugarcoating, even his own cryptocurrency with no crypt about it. As for the use of power, it’s been an iron fist in an iron glove.

I take a smidgen of comfort in polls that show his popularity is tanking. But will it matter what the public thinks? If it’s still possible to vote freely and meaningfully in 2028—a dubious proposition—will we already be dead from the next pandemic that the decimated CDC didn’t warn us about?

Wait, look up—is that the sky falling?

To Stab or Not to Stab

August 7, 2025

“It became necessary to destroy the town to save it,” said an unnamed U.S. major, as reported by journalist Peter Arnett in 1968, describing the obliteration of more than 5,000 homes in one town, Bến Tre, during the Vietnam War. Widely publicized, though often misquoted, this justification for savagery was soon condemned. But does the same idea, wreck-it-to-save-it, now apply to democracy in America?

With Republicans determined to reshape congressional districts in multiple red states to guarantee their continued dominance of the U.S. House, Democrats are threatening to do the same in reverse in states they control. Is the Democrats’ response justified?

Redistricting—drawing a bunch of district maps to divvy up a state—is a complicated process. Since there are many measures for judging the fairness of a map, there’s usually enough of a fudge factor to allow a pretense of equity even when the results are biased. Not this time. This is pure partisan gerrymandering, all its naked parts hanging out in public view, with not even a scrap of gauzy film for modesty.

Of course, the Republican effort to subvert democracy serves the purposes of the would-be autocrat in the White House, known on this blog as Resident Ronald Rump, a.k.a. the Big Rump or Rumpy. Since he’s already responsible for many thousands of deaths (by decimating U.S AID, cutting Medicaid, supporting genocide in Gaza, etc. etc.), a gerrymandered stab at democracy’s liver seems abstract in comparison. But if he undermines the process, there will be fewer restrictions on him in the future. That’s why this may be a crucial turning point.

So let’s face the question: Is it necessary for Democrats to undercut the democratic process in order to save it? We’re “at war,” says New York’s Democratic governor, Kathy Hochul. And most folks, however pacific their nature, believe that war is sometimes necessary. Or revolution, if the oppression is bad enough. Wars and revolutions kill and injure innocent people, but they are often justified as a way to prevent greater damage.

We firebombed Dresden to stop Hitler (see the photo). We nuked Hiroshima to stop Japan. We set moral doubts aside to be examined later.

This is where we find ourselves as we debate whether to smash democratic norms in order to save them.

Democrats on the “war” footing insist that we can merely suspend democracy, temporarily and in certain places, to keep Republicans from ravaging it permanently. Is that sensible?

To me, the decision depends in part on how dire the danger is.

If, say, it becomes evident that Rumpy and his minions will cancel the presidential election in 2028, then we can’t stand on principle, we have to fight with whatever weapons we can muster. Revolution, if it comes to that.

But suppose we believe that Rumpy’s depredations are reversible. Whatever harm he does, we may think the next president can fix it. Is that a legitimate thought when children are literally dying because of his actions? Dead kids, unfortunately, can’t be resurrected.

But wait, let’s not get distracted by those piles of dead bodies. The issue here is whether Democrats should break their democratic principles to prevent worse injury to our nation. So we have to phrase the question this way: If both parties jointly knife our system in the ribs, will the wounds eventually heal? Is there such a thing as a “temporary” suspension of democracy? How long will that last? What else may be lost along the way?

I confess I’m flummoxed. This issue is too difficult for me to grasp, even aided by a tall glass of whiskey.

Three Truths for the Fourth

July 4, 2025

My typical practice for holidays is to ignore them. As a dedicated melancholic, I’m not big on celebrations of any sort.

Nevertheless, this Independence Day seems worth marking. It’s the day Trump signs his Big Beautiful Bill to benefit the obscenely wealthy while sentencing millions of low-income Americans to death from lack of medical care. Though the bill is unpopular with the public, the political consequences are uncertain. Thus it’s worth asking why politicians who enact unpopular, even disastrous policies gain power in what is supposed to be a democracy.

I won’t rehash the standard answers to that question: big campaign donors, PACs, gerrymandering, etc. etc. But after the 2024 presidential election, it seemed to me that three fundamental lessons were evident. These lessons are pretty much common knowledge, but they tend to be overlooked by party leaders and pundits who focus on strategic and tactical issues.

Since last November we have been buried in endless, detailed analysis of what Biden did wrong, what mistakes Harris made, and how Trump and his minions played on fears of made-up bogeymen like immigrants and socialists. I’m looking instead at long-term qualities of American society, and American voters, that change very little from one election to the next.

1. Americans are still racist and sexist.

True, in presidential voting, we overcame racism twice with Obama, who was an extraordinary politician with relatively weak opposition; and we beat sexism once when Hillary Clinton took the popular vote in 2016. But conquering both prejudices was simply too much for Kamala Harris, as evidenced by the anecdotes about Black men who thought she was incapable of standing up to Putin. (It probably didn’t help that she’s slim and pretty; if she’d been built like Angela Merkel, she might have been judged more formidable.)

The effects of prejudice on a voter can be quite subtle: a slight, unarticulated reluctance to trust a candidate, or an increased willingness to entertain doubts or slanders. In a campaign full of outrageous lies, this can be enough to change a vote or convince a person to skip voting entirely.

I’m not a pollster, but broadly speaking, I’d say the numbers for Democrats look like this: Nationally, about 45% of votes are automatically lost because of the party label. A Black candidate loses another 3%, a woman 2%. It’s only the undemocratic Electoral College that matters, of course; yet it’s clear that any Democrat other than a white male faces long odds.

Make that a white straight male. We haven’t tested the prejudice against LGBTQ+ folks in a presidential election, but I suspect the numbers are about the same.

Would there be a similar bias against a Jewish candidate? My Jewish wife thinks so. As for a Muslim or Buddhist … let’s not even go there.

This is such a terrible state of affairs that I hope my reasoning is wrong. But we need to face the strong possibility that it’s right.

2. Voters are selfish.

Besides being a truism, this is often considered a positive feature of democracy. I vote for what’s good for me, you vote for what’s good for you, and the overall outcome is what’s best for the majority. But we often fail to realize the supreme dominance of selfishness and the narrow way it functions.

Democrats like myself supported Harris for noble reasons that simply didn’t play with the larger public. For instance, we were taken with grand ideas like these:

a. Preserving democracy against an existential threat. This argument was much too abstract for many voters, even those not attracted by strong-man vibes.

b. Maintaining support for Ukraine. Ukraine is too far away. Europe is too far away. Most American voters may support Ukraine in principle, but at least half don’t fundamentally care.

c. Restraining the genocide in Gaza. Though Biden certainly gave Israel a lot of leeway to kill Palestinian civilians, it was clear that Trump would be even less likely to restrain Israeli hardliners. Yet many voters paid little attention to this issue. Dead Palestinians, so what?

Then what did voters care about? “The price of eggs” became the pop shorthand answer.

Think about how deeply, deeply selfish this is. That’s how people tend to vote.

3. American voters are ignorant.

Many Trump voters were not just ill-informed about the issues and the candidates. They were abysmally ignorant. Things they didn’t know included:

- The foreseeable effect of Trump’s tariffs on inflation, raising “the price of eggs.” Economists kept pointing this out, but Trump voters didn’t hear it or didn’t grasp it.

- The predictable effects of implementing Project 2025, decimating the federal programs that benefit most Americans and undermining the economy for many years to come.

- The likely savagery and economic upheaval of Trump’s plan to deport undocumented immigrants.

Zohran Mamdani, running for mayor of New York, tells of speaking to voters who said they supported Trump because, four years earlier, they had less trouble making ends meet. These people aren’t, by and large, stupid, but they reason in an utterly stupid way; they take hold of one salient idea and block out any qualifiers.

Some of the problem can be attributed to the fragmentation of news sources. I’m old enough to remember the angst of intellectuals when Americans began to gather most of their news from short-form TV programs rather than newspapers and magazines. Yet, from our current perspective, the 1960s and 1970s were far more enlightened. The news shows from the three major networks hewed to a fairly centrist line, and when Walter Cronkite concluded his broadcast by saying, “And that’s the way it is,” he was telling the truth: indeed, that was how it was, more or less, and at the peak of network news, more than 50 million Americans heard it from him or his fellow broadcasters. Now, for large portions of the populace, Walter has been replaced by biased, conspiracy-peddling media pundits.

Many Americans, of course, are willfully ignorant, refusing to attend to any media that don’t confirm their ingrained beliefs. I have to admit that I do not, and will not, watch Fox News, so I remain oblivious to any scrap of truth purveyed by that outlet.

Another reason for mass ignorance may be the decline of civics education in schools. That’s something we might tackle, but oops, the folks in power don’t believe in education, do they?

Whatever the origin, ignorant citizens are a condition we must contend with for years, probably decades, to come. Our leaders will be elected in large part by people who don’t know shit. If you think that sounds elitist, I counter by saying that, yes, it’s elitist and also true.

So these three points, I believe, are fundamental lessons for the Democratic party and any other group that would like to preserve what’s left of our democracy. You have to deal with racism and sexism, appeal to narrow selfish concerns, and overcome colossal ignorance. Among our goodhearted compatriots, who’s ready to tackle such a task?

Civil Rights vs. Religion

December 18, 2022

The controversy caused by Lorie Smith, an anti-gay Colorado website designer, has prompted me to think through my position on the issues she raises—issues that pit her religious beliefs against the rights of her (hypothetical) customers. Some of my liberal friends, predictably, have lined up against her. Though I’m way-left on the political spectrum, I don’t find the matter so simple.

To review the situation: Planning to expand her business to include wedding websites, Smith has preemptively sued the state to prevent it from charging her with discrimination if she declines to serve gay couples on account of her religious principles. The U.S. Supreme Court has heard the case and is expected to rule by the end of its current term.

Given Colorado’s actions in the 2018 Masterpiece Cakeshop case, maybe Smith has grounds for worry. In the Masterpiece case, the Colorado Civil Rights Commission ruled against a baker who refused to design a wedding cake for a gay couple, and the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which decided in the baker’s favor.

Of course there’s a large element of political grandstanding in cases like these. They’re based on situations that would never occur in daily life. Any self-respecting gay couple wouldn’t let that baker anywhere near their cake, nor would they let Lorie Smith have a byte of their website.

Still, in spite of the political flapdoodle, cases that pit one person’s rights and moral/religious beliefs against another’s deserve some thought. Imagine a gynecologist who believes that abortion is murder. Would you force her or him to perform an abortion when neither the woman’s nor fetus’s health or welfare demanded it? I wouldn’t, and most Americans probably agree with me on that. Yet if the woman’s life was in danger, the operation had to be done immediately, and no other doctor was available, my opinion would change.

So where do we draw the line? How do we balance the conflicting rights and moralities?

My thinking has coalesced into what could be called a three-pronged test, a term with a nice legal ring to it. Perhaps because they have spiky personalities, judges favor tests with prongs.

Let’s call the parties the Provider and the Customer. Here are the three aspects of the test:

1. The nature of the moral/religious objection. Is the Provider’s disapproval of the Customer based on the latter’s behavior or on unchangeable attributes? It could be that Ms. Smith and some of her right-wing supporters don’t like serving African Americans, but they have enough sense to realize they’d get no sympathy for such a stance, even if they claimed a religious basis for it. People can’t choose their race or skin color. By targeting gays, conservatives are picking a group that engages in behavior they condemn. Yes, LGBTQ folks contend, with reason, that they are born with their gender and sexual preferences, but they don’t have to get married, nor do they even have to have sex. It is, whether we progressives like it or not, a question of their behavior. Passing this behavior test is a precondition for moving on to prongs 2 and 3.

2. The Provider’s degree of involvement with the Customer.

2a. Is the Provider’s involvement passive or active? Jack Phillips, the cakeshop owner, could have no legitimate objection if a gay couple came into his shop and bought a cake from the display case. He probably wouldn’t know they were gay, and even if they identified as such and smooched in front of him, his involvement with them would be minimal: lifting the cake from the case, boxing it, ringing up the sale. In contrast, when they asked him to design a custom cake for them and have it ready on a certain day, they were demanding he take an active role in their wedding, even a “creative” one.

2b. If the involvement is active, to what degree does it involve direct participation in the disapproved behavior? Imagine that Phillips had been asked not just to design and bake the wedding cake in the back room of his shop, but to help cater the event—to come out to the wedding venue, preside over the ceremonial slicing of the cake, and serve the guests? That would be a greater degree of involvement in celebrating an action he considered immoral. An even better example is a wedding photographer who interacts personally and repeatedly with the couple and their relatives and guests.

At step 2a, if the involvement is active rather than passive, I begin to favor the Provider’s point of view, and at 2b I definitely side with him or her. In my daily work, I offer book production services to clients of various backgrounds. If Paul Manafort asked me to edit, design, and print his next memoir, which I suppose should be called A Sleazeball’s Campaign Against Truth and Decency, I’d refuse him on moral grounds. Luckily, sleazeballs are not a protected class, so the law couldn’t compel me.

3. The extent to which the Provider’s service is vital to the Customer’s well-being. I suppose most people take wedding cakes and websites far more seriously than I do. Frankly, I consider them trivial, and my own wedding was the opposite of ceremonial. We didn’t have a cake or website, and we’ve done fine without. Since services like that are not vital—and, besides, are available from multiple vendors—I think the Provider should be free to refuse them even for relatively minor reasons. The opposite would be true of the gynecologist mentioned earlier—the only doctor available when the patient’s life is at stake. In that case, the Customer’s great need should prevail over the Provider’s sense of morality.

Finally, there’s an underlying thought at work here. Most of us get very annoyed when government regulations restrict us personally. We especially hate bureaucrats and their nitpicking, irrational rules. Yet we don’t mind it much when the government restricts others. Let’s keep that in mind. Whatever we think of bigoted bakers and website designers, we should recall that they believe what they believe, and what a government can do to them it might possibly, under other circumstances, do to us.

Susie’s e-book

July 30, 2022

Susie Alioto, the namesake protagonist of The Bourgeois Anarchist, may be 66 years old and struggling a bit with her health, but she’s always been up-to-the-moment, so it’s no surprise that her story is now available in a Kindle-type ebook. The co-protagonist, her math-geek son Eric, ridicules her for surrendering to such a gross and uncool form of capitalism. But to understand the odd balance of their relationship, as well as Susie’s complicated links with her anarchist heroes, you’ll have to read the book.

(NB: Susie may be visible in the cover image, which shows a protest march somewhere in the world on some recent date. Details are blurred to protect the guilty.)

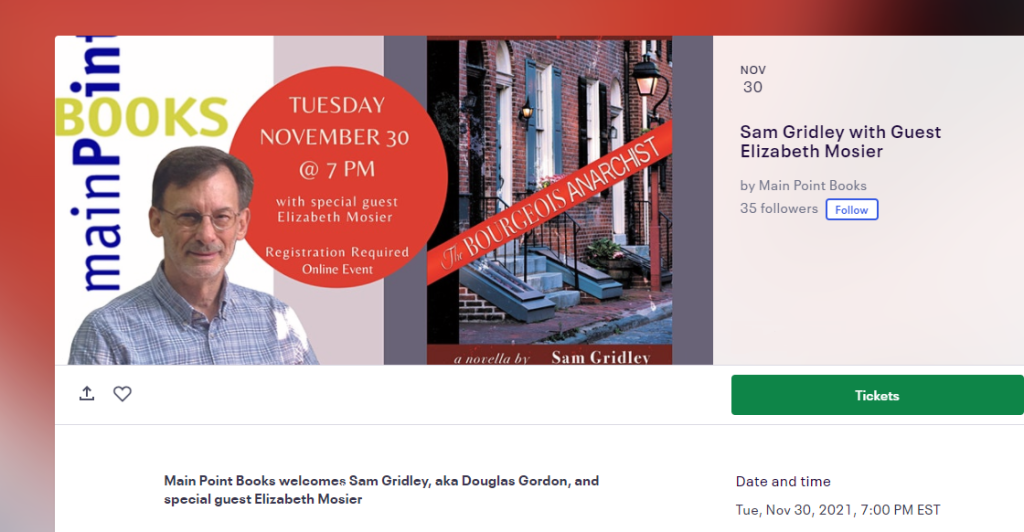

Book Launch

November 23, 2021

We’ll be officially launching The Bourgeois Anarchist on November 30, 2021, via Zoom, at 7 p.m. Eastern.

Being a taciturn curmudgeon, I’m extremely lucky to be joined by Elizabeth (Libby) Mosier, an extraordinary writer who’s a much better conversationalist than I am. Most likely, Libby will ask intelligent questions to which I will give confused, nonsensical answers. It should be fun!

To witness this spectacle, and maybe ask questions of your own, you have to register in advance for the Zoom link. The event will be hosted by our friends at Main Point Books in Wayne, PA, which is offering signed copies of the book.

Blurred Choices

November 17, 2021

Ellen Prentiss Campbell, an award-winning fiction writer and member of the National Book Critics Circle, has kindly reviewed The Bourgeois Anarchist in Tiferet Journal. Throughout the novella, she notes, “the lines between good and bad, right and wrong, blur”–proving she firmly grasped the book’s main theme.

Though the magazine is available by subscription only, I can offer a quote from the end of the piece, summarizing her take on the 66-year-old protagonist, Susie Alioto:

Susie is an irresistible force. Readers, especially those of a certain age, aficionados of Anne Tyler’s quirky heroines, will enjoy Susie. She carries the baggage of years of living and experience with almost reckless, youthful abandon. And begins to reckon with some skeletons in her own closet and to figure out what’s next.

You can purchase the novella on Bookshop.org.

Advance Praise for Susie’s Story

July 19, 2021

After some production struggles, my novella The Bourgeois Anarchist, featuring 66-year-old militant Susie Alioto, is on track to be released this fall by Finishing Line Press. You can order the book at the publisher’s site, and it will soon be available on Amazon, Bookshop.org, and elsewhere.

Oddly, I haven’t yet boasted about what my distinguished writerly acquaintances have said about the book. I’ll make up for that right now. Here’s the advance praise that’s come in so far (and if you’d like to add to it, feel free, especially if you have a million Twitter followers):

The Bourgeois Anarchist is an engrossing tale of an aging pacifist’s struggle to live her ideals as she’s enveloped by the dangers of anarchic activism and the violence of big city capitalism.

—Alan Drew, author of Shadow Man and Gardens of WaterIf you’ve ever wondered what you would do in a time of crisis … you’re doing it right now. Susie Alioto is doing her thing too … marching, banner-waving and trying to reconcile her anarchic principles with her non-violent beliefs, in an America where non-violence seems to be increasingly impossible. As tensions rise in her rapidly gentrifying district of Philadelphia, a motley crew of cops, mobsters, pacifists and pseudo-anarchists invade Susie’s quiet existence. No wonder she’s feeling dizzy. A thoroughly enjoyable, and surprisingly gentle, story of love, duty and politics.

—Orla McAlinden, author of The Accidental Wife and The Flight of the WrenWhen it comes to political convictions, our younger selves are bound to judge our older selves, and harshly. The charm of this novella is the way it presents this subject with such a light touch, such generosity, and such affection for its characters.

—Simone Zelitch, author of Judenstaat, Waveland, and LouisaIt’s antifa vs artisanal coffee in this absorbing and timely Philadelphia story about the difficulties of living out one’s radical principles in the most orderly way possible.

—Elisabeth Cohen, author of The Glitch

An earlier post included an image of a poster Susie keeps on her refrigerator: a portrait of her special anarchist hero, Errico Malatesta (a real historical figure), with his most famous saying, “Impossibility never prevented anything from happening.” When I wrote the book, this poster did not actually exist, so I created it. Anyone who requests it via the Contact page can have a high-res JPEG or PDF copy for free, to post in the kitchen (to puzzle friends) or on the front door (to attract police scrutiny).