To Stab or Not to Stab

August 7, 2025

“It became necessary to destroy the town to save it,” said an unnamed U.S. major, as reported by journalist Peter Arnett in 1968, describing the obliteration of more than 5,000 homes in one town, Bến Tre, during the Vietnam War. Widely publicized, though often misquoted, this justification for savagery was soon condemned. But does the same idea, wreck-it-to-save-it, now apply to democracy in America?

With Republicans determined to reshape congressional districts in multiple red states to guarantee their continued dominance of the U.S. House, Democrats are threatening to do the same in reverse in states they control. Is the Democrats’ response justified?

Redistricting—drawing a bunch of district maps to divvy up a state—is a complicated process. Since there are many measures for judging the fairness of a map, there’s usually enough of a fudge factor to allow a pretense of equity even when the results are biased. Not this time. This is pure partisan gerrymandering, all its naked parts hanging out in public view, with not even a scrap of gauzy film for modesty.

Of course, the Republican effort to subvert democracy serves the purposes of the would-be autocrat in the White House, known on this blog as Resident Ronald Rump, a.k.a. the Big Rump or Rumpy. Since he’s already responsible for many thousands of deaths (by decimating U.S AID, cutting Medicaid, supporting genocide in Gaza, etc. etc.), a gerrymandered stab at democracy’s liver seems abstract in comparison. But if he undermines the process, there will be fewer restrictions on him in the future. That’s why this may be a crucial turning point.

So let’s face the question: Is it necessary for Democrats to undercut the democratic process in order to save it? We’re “at war,” says New York’s Democratic governor, Kathy Hochul. And most folks, however pacific their nature, believe that war is sometimes necessary. Or revolution, if the oppression is bad enough. Wars and revolutions kill and injure innocent people, but they are often justified as a way to prevent greater damage.

We firebombed Dresden to stop Hitler (see the photo). We nuked Hiroshima to stop Japan. We set moral doubts aside to be examined later.

This is where we find ourselves as we debate whether to smash democratic norms in order to save them.

Democrats on the “war” footing insist that we can merely suspend democracy, temporarily and in certain places, to keep Republicans from ravaging it permanently. Is that sensible?

To me, the decision depends in part on how dire the danger is.

If, say, it becomes evident that Rumpy and his minions will cancel the presidential election in 2028, then we can’t stand on principle, we have to fight with whatever weapons we can muster. Revolution, if it comes to that.

But suppose we believe that Rumpy’s depredations are reversible. Whatever harm he does, we may think the next president can fix it. Is that a legitimate thought when children are literally dying because of his actions? Dead kids, unfortunately, can’t be resurrected.

But wait, let’s not get distracted by those piles of dead bodies. The issue here is whether Democrats should break their democratic principles to prevent worse injury to our nation. So we have to phrase the question this way: If both parties jointly knife our system in the ribs, will the wounds eventually heal? Is there such a thing as a “temporary” suspension of democracy? How long will that last? What else may be lost along the way?

I confess I’m flummoxed. This issue is too difficult for me to grasp, even aided by a tall glass of whiskey.

Swerving from the Hurricane

August 28, 2011

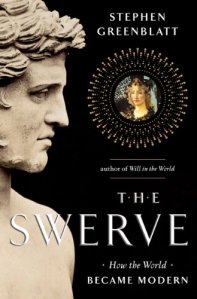

In the past week, while dealing with earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, a lame dog, and fears of a second recession, I had the chance to read Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. Perhaps this proves that I have the same response to potential calamity as Art Dennison, the protagonist of my most recent novel: hide in a quiet room and read.

In the past week, while dealing with earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, a lame dog, and fears of a second recession, I had the chance to read Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. Perhaps this proves that I have the same response to potential calamity as Art Dennison, the protagonist of my most recent novel: hide in a quiet room and read.

After I was intrigued by a piece based on Greenblatt’s book in the August 8 New Yorker (article summary here), a friend kindly passed along an advance reading copy. A Harvard scholar, Greenblatt is known for what I would call crossover works, ones that combine scholarship with popular appeal. His previous book, Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, made a splash by combining Bard biography with a colorful portrait of Elizabethan England. In The Swerve he takes two historical figures about whom even less is known, the Latin poet Lucretius and the fifteenth-century papal secretary Poggio Bracciolini, and spiraling outward from those two, spins an intriguing tale of Classical philosophy, medieval copyists, Renaissance book hunters, and radical changes in the way we look at the world.

Intellectual history is great fun when written well, and Greenblatt is one of the best at it. His central point is that Poggio’s accidental discovery of a complete version of Lucretius’ De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things)—accidental in that Poggio was combing monastery libraries for copies of ancient texts but not that one in particular—played a central role in breaking down medieval religious thought and freeing the great minds of the Renaissance. It’s long been known that Lucretius influenced the humanists, but Greenblatt implies that this one masterful poem, in which Lucretius expounds on the Epicurean vision of the universe, smashed more barriers than any other Renaissance rediscovery and thus opened a broad road to modernity. Though I don’t know how many scholars of the period will grant Lucretius this extraordinary importance, I’m personally willing to allow it for the sake of the story.

One chapter offers an extended bullet list of the “elements that constituted the Lucretian challenge” to Church-molded thought. Here are some of the bullet points, without the author’s commentary:

- Everything is made of invisible particles. [Lucretius didn’t call them atoms, but he was drawing on the atomism of Democritus and others.]

- All particles are in motion in an infinite void.

- The universe has no creator or designer.

- The universe was not created for or about humans.

- Humans are not unique.

- The soul dies.

- There is no afterlife.

- All organized religions are superstitious delusions.

- The highest goal of human life is the enhancement of pleasure and the reduction of pain.

From a churchman’s point of view, this list moves from suspicious to upsetting to burn-at-the-stake heretical, and of course many humanists played with these notions without committing outright to them. Still, even with clever concealments and subtle emendations, such ideas had the power to swerve society from medievalism toward modernity.

Greenblatt emphasizes that the Lucretian version of Epicureanism, like Epicurus’ own, did not equate living for “pleasure” with pursuing uninhibited passions and impulses. Rather, the highest pleasure comes from philosophical contemplation that “awakens the deepest wonder.” Kind of like hiding in your room to read while the hurricane roars by.

For me, one takeaway from this book is the renewed realization that human thinking goes in cycles, with old notions constantly being resurrected and reshaped. The body and soul may both dissolve into the mud, but ideas get into the water table and seep out in strange new places.

In fact, I’ve recently unearthed in the basement of my ancient house a mildewed manuscript that disintegrated as soon as I touched it. Only a few fragments remain legible, one of which seems to be attributed to a certain Sammus Gridlius, a previously unknown scribe of the first century A.D. Roughly translated from the Latin, it goes like this:

All that’s thunk has been thunk before. All that’s writ has been writ before. Peace, brother.

Circumstantial evidence indicates that a rediscovery of this text by John Lennon in 1968 influenced the late Beatles songs and consequently all of contemporary culture. I’m still working on proof for that theory.