Travels with Alice

October 12, 2011

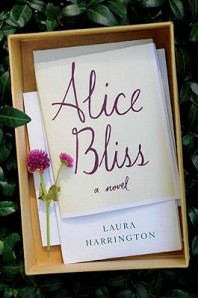

A Bookcrossing “travelling book” recently came my way: a copy of Laura Harrington’s new novel Alice Bliss. Bookcrossing.com encourages readers to pass along their books, either to acquaintances or to strangers, and then track them to see where they end up. The site supplies tracking numbers along with labels to paste inside a book. Harrington’s publisher, Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, has sent out some prelabeled copies to bloggers to begin the process for Alice Bliss. The idea is to give Alice, a 15-year-old from Massachusetts, a tour of the world. Currently, according to the website, she has reached 30 states and five continents. I suspect my handoff won’t add another state or continent, but I will surely pass the book on.

A Bookcrossing “travelling book” recently came my way: a copy of Laura Harrington’s new novel Alice Bliss. Bookcrossing.com encourages readers to pass along their books, either to acquaintances or to strangers, and then track them to see where they end up. The site supplies tracking numbers along with labels to paste inside a book. Harrington’s publisher, Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, has sent out some prelabeled copies to bloggers to begin the process for Alice Bliss. The idea is to give Alice, a 15-year-old from Massachusetts, a tour of the world. Currently, according to the website, she has reached 30 states and five continents. I suspect my handoff won’t add another state or continent, but I will surely pass the book on.

In a reversal of the typical process, this novel grew out of a musical, Alice Unwrapped, a solo piece that has been performed in New York and Minneapolis. Harrington won a 2008 Kleban Award for the libretto. The tale is a modern-day version of the homefront story—what goes on at home when the men march off to war. And indeed it is the man, Alice’s father Matt, who flies off to Iraq, leaving his wife and two daughters to fend for themselves. They have the support of a grandma, an uncle, and various friends, all of whom prove vital to the family’s well-being.

Somewhat alienated from her mother, teenaged Alice is especially close to her father, who has taught her gardening, baseball, roofing, puttering around a workshop, and other important life skills. Once he’s gone, she wears an old shirt of his every day and insists on planting the garden, by herself, exactly as he would have done it. Her mother worries about Alice’s obsessions but clearly has struggles of her own.

During this stressful time, Alice is also developing feelings about boys, two of them in particular, who provide exciting, ambivalent, and incoherent substitutes for her missing father. Unaccustomed to girl-coming-of-age stories, I found it comforting to discover (if Harrington can be believed) that girls are almost as stupid in their first romances as boys. There are many funny, poignant moments as Alice wavers between the nerd she’s known since childhood and the popular hunk who suddenly notices her.

Though the novel dives deep into Alice’s psyche, Harrington skips on occasion into other points of view, and she does this skillfully enough that I didn’t feel jarred. There are bits seen from the viewpoint of Alice’s mother, her comical Uncle Eddie, and her proto-boyfriend Henry. Although a few of these asides seem unnecessary, they generally add to our understanding of the characters.

The novel’s world, rich as it is, is limited in certain ways: Aside from Eddie, a cool variant of everyone’s disreputable uncle, grown men are scarce in this story. Aside from the war overseas, evil is even scarcer. Everybody is well-meaning. All are trying to make things work. Nobody is inordinately selfish. And yet this world seems true to life—even when everybody means well, suffering happens.

Alice Bliss is an accomplished novel, remarkably so for the author’s first effort in this genre. Though the main audience will surely be female, men won’t be injured by perusing the book, I promise. Maybe men with teenaged daughters will even learn something useful.

Visiting a Playgroup

September 22, 2011

Recently I’ve been learning about motherhood. Being a father of two and grandfather of five and a half,* I never expected to study mothering except for the few tricks a man needs to know for self-preservation. But reading Elizabeth Mosier’s The Playgroup (part of GemmaMedia’s Open Door series) was entertaining as well as enlightening.

Recently I’ve been learning about motherhood. Being a father of two and grandfather of five and a half,* I never expected to study mothering except for the few tricks a man needs to know for self-preservation. But reading Elizabeth Mosier’s The Playgroup (part of GemmaMedia’s Open Door series) was entertaining as well as enlightening.

The novella (110 pages) focuses on a group of women who have set up a Playgroup ostensibly for their infants, but really to give the mothers a chance to schmooze. And their talk, as Mosier details it, is alternately funny, unsettling, profound, trivial, and full of annoying advice about child-proofing the house. What comes through most strongly is an undercurrent of fear—that a mother will fail at her awesome responsibilities or that this carefully arranged but fragile life will take a gruesome turn. The protagonist, Sarah, pregnant with her second child, has a special dread caused by an abnormality in her sonogram, a small spot “shaped like a cashew.” But uncertainty governs even the most outwardly self-confident of the women:

“Motherhood is like a second adolescence, a time when the self a woman thinks she owns is repossessed by the so-called authorities [all the experts, including family members, who tell her how to be a mother]. She’s left naked and defenseless, asking herself questions about purpose, faith and identity she thought she’d already tamed. … At times, we seemed less like mothers than like insecure teenagers at a beer keg tapping liquid courage, though at Playgroup we swilled coffee while we sought each other’s advice.” (pp. 11–13)

“Loss always lurked beneath our conversations in Playgroup, under talk of microdermabrasion, premenopausal symptoms, IRAs and long-term health insurance.” (p. 72)

The book has one symbolically “perfect” mother, Amy Marley (name reminiscent of Jacob Marley, one of the ghosts in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol), who comes back to haunt the others in an unexpected way, and the arc of her life becomes instructive to all.

During a recent reading at Philadelphia’s Musehouse, the author explained that details of the new mothers’ thoughts and emotional swerves are based on notes she took at that stage of her life. She was brutally honest with herself back then, and her readers get the benefit now.

To give us multiple views of the Playgroup in a short space, Mosier employs a clever narrative device. The first-person narrator, Laurie, begins as a relatively undifferentiated member of the group, and as such she gives us the community outlook on the main character, Sarah:

“Sarah led us into the living room, an arrangement of white chairs and a couch on a white pile rug. … Another group, gathered for a different purpose, might have praised the room’s stark furnishings, but we were there to compare and to judge. Sarah waited nervously for our review.”

Soon, however, Laurie becomes a confidante of Sarah’s, able to reveal Sarah’s thoughts and feelings. Though I was a little less than 100% convinced by this dual narrative function, it should work for 99.9% of readers.

The men in these women’s lives are mostly ignored and irrelevant in the story; they pour margaritas and hammer away at construction projects. Yet the only time I wanted to escape the estrogen-laden environment was when the women started scrapbooking—an activity that, to my relief, the narrator treated with irony.

The book is a quick and fascinating read, and I recommend it to all men who are partnered with a mother, who work with mothers, who stumble upon unfathomable claques of mothers and infants at coffee shops, or who wish to understand why mothers behave in an irrational manner so totally unlike our time-honored male form of irrationality.

*Three dogs, one long-term cat, one short-term cat recently expelled from the immediate family (that’s the half), and one snake. At last count.

Measures of Disobedience

August 30, 2011

Last night I finished Ru Freeman’s novel A Disobedient Girl, which is composed of two interlocking narratives about Sri Lankan women trying to break loose from the stifling conventions of marriage and caste. This book has a lot to recommend it. To me, one striking feature is not the obvious similarity between the two female protagonists, both of whom are seeking freedom, but rather their difference.

Last night I finished Ru Freeman’s novel A Disobedient Girl, which is composed of two interlocking narratives about Sri Lankan women trying to break loose from the stifling conventions of marriage and caste. This book has a lot to recommend it. To me, one striking feature is not the obvious similarity between the two female protagonists, both of whom are seeking freedom, but rather their difference.

In one story line, Biso, a devoted mother of three, leads her brood in a flight from their abusive father; she’s close to 100 percent good, without a nasty thought in her brain. Though she cheated on her husband, he deserved it. The other protagonist, Latha, a servant girl, whom we follow from childhood to her thirties, is not just “disobedient” as the title proclaims, but genuinely nasty at times; she has a penchant for disloyalty, revenge, sneakiness, and deceit.

With Latha, the author herself is being disobedient to the standard portrayal of a female heroine. True, Latha is no Emma Bovary; she’s more pleasant than Emma, smarter, more honest with herself. Still, we’re asked to admire a character who takes some malicious whacks at those around her—and we do. We like her spirit, and we sympathize with her bondage. Orphaned, she was taken as a young child into an upper-class home, where she was raised with another girl her own age, Thara. She and Thara become close friends, but the caste difference can never be shaken, and ultimately she takes the role of Thara’s servant. Their love/hate relationship forms the core of the novel.

We also admire Latha for her passionate dedication to Thara’s children, whom she treats as her own. Like Biso, she has mothering instincts that are fervent, tough, resilient. In this book, it’s only the spoiled high-caste twits who make bad mothers.

In contrast to the women, the adult males in both story lines tend to be distant and/or beastly, and I found that a bit disappointing. Both plots end melodramatically, too, with some twists that I found unlikely. But the sharp details of Sri Lankan family life more than make up for any distortions of realism in the plotting, as does the complex psychology of the bond between Latha and Thara.

Since I read this book in an electronic version on a Nook (the popular Barnes & Noble e-reader), I have to point out that many of the special characters in the Sri Lankan terms did not translate—they appeared as question marks. They may be fine in the epub file itself, but they don’t display on the Nook. The publisher, Atria, is a division of Simon & Schuster, and with that major house’s resources, the editors ought to be able to pay someone to check a book’s appearance on the most common e-readers. If an accented character doesn’t display properly, a workaround can be found—at the very least, the substitution of a standard keyboard letter.

Swerving from the Hurricane

August 28, 2011

In the past week, while dealing with earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, a lame dog, and fears of a second recession, I had the chance to read Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. Perhaps this proves that I have the same response to potential calamity as Art Dennison, the protagonist of my most recent novel: hide in a quiet room and read.

In the past week, while dealing with earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, a lame dog, and fears of a second recession, I had the chance to read Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. Perhaps this proves that I have the same response to potential calamity as Art Dennison, the protagonist of my most recent novel: hide in a quiet room and read.

After I was intrigued by a piece based on Greenblatt’s book in the August 8 New Yorker (article summary here), a friend kindly passed along an advance reading copy. A Harvard scholar, Greenblatt is known for what I would call crossover works, ones that combine scholarship with popular appeal. His previous book, Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, made a splash by combining Bard biography with a colorful portrait of Elizabethan England. In The Swerve he takes two historical figures about whom even less is known, the Latin poet Lucretius and the fifteenth-century papal secretary Poggio Bracciolini, and spiraling outward from those two, spins an intriguing tale of Classical philosophy, medieval copyists, Renaissance book hunters, and radical changes in the way we look at the world.

Intellectual history is great fun when written well, and Greenblatt is one of the best at it. His central point is that Poggio’s accidental discovery of a complete version of Lucretius’ De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things)—accidental in that Poggio was combing monastery libraries for copies of ancient texts but not that one in particular—played a central role in breaking down medieval religious thought and freeing the great minds of the Renaissance. It’s long been known that Lucretius influenced the humanists, but Greenblatt implies that this one masterful poem, in which Lucretius expounds on the Epicurean vision of the universe, smashed more barriers than any other Renaissance rediscovery and thus opened a broad road to modernity. Though I don’t know how many scholars of the period will grant Lucretius this extraordinary importance, I’m personally willing to allow it for the sake of the story.

One chapter offers an extended bullet list of the “elements that constituted the Lucretian challenge” to Church-molded thought. Here are some of the bullet points, without the author’s commentary:

- Everything is made of invisible particles. [Lucretius didn’t call them atoms, but he was drawing on the atomism of Democritus and others.]

- All particles are in motion in an infinite void.

- The universe has no creator or designer.

- The universe was not created for or about humans.

- Humans are not unique.

- The soul dies.

- There is no afterlife.

- All organized religions are superstitious delusions.

- The highest goal of human life is the enhancement of pleasure and the reduction of pain.

From a churchman’s point of view, this list moves from suspicious to upsetting to burn-at-the-stake heretical, and of course many humanists played with these notions without committing outright to them. Still, even with clever concealments and subtle emendations, such ideas had the power to swerve society from medievalism toward modernity.

Greenblatt emphasizes that the Lucretian version of Epicureanism, like Epicurus’ own, did not equate living for “pleasure” with pursuing uninhibited passions and impulses. Rather, the highest pleasure comes from philosophical contemplation that “awakens the deepest wonder.” Kind of like hiding in your room to read while the hurricane roars by.

For me, one takeaway from this book is the renewed realization that human thinking goes in cycles, with old notions constantly being resurrected and reshaped. The body and soul may both dissolve into the mud, but ideas get into the water table and seep out in strange new places.

In fact, I’ve recently unearthed in the basement of my ancient house a mildewed manuscript that disintegrated as soon as I touched it. Only a few fragments remain legible, one of which seems to be attributed to a certain Sammus Gridlius, a previously unknown scribe of the first century A.D. Roughly translated from the Latin, it goes like this:

All that’s thunk has been thunk before. All that’s writ has been writ before. Peace, brother.

Circumstantial evidence indicates that a rediscovery of this text by John Lennon in 1968 influenced the late Beatles songs and consequently all of contemporary culture. I’m still working on proof for that theory.

Sons and Heirs: Lorene Cary’s Latest

August 7, 2011

Recently I finished Lorene Cary’s latest novel, If Sons, Then Heirs, another fine and highly readable book from one of Philadelphia’s most respected authors. Lorene is well known locally for her community work with the Art Sanctuary, but as a reader I’m happy to see she’s not neglecting her own writing.

Recently I finished Lorene Cary’s latest novel, If Sons, Then Heirs, another fine and highly readable book from one of Philadelphia’s most respected authors. Lorene is well known locally for her community work with the Art Sanctuary, but as a reader I’m happy to see she’s not neglecting her own writing.

Featuring several generations of a single family, If Sons, Then Heirs combines a fairly simple present-day story with an intricate and complex revelation of the family’s past. The genealogical tree that appears early in the book should help readers keep track of the many characters who roam the pages. Unfortunately, I read the Nook e-book version, on which the chart is illegible, and so I was constantly struggling to remember, for instance, how Binkie is related to Lil Tootchie. (Great names throughout!)

Roughly, the present-day plot goes like this: Rayne, an African American man who runs a construction business in Philadelphia, stands to inherit the old farm on which his great-grandmother, Selma, is living in South Carolina. Yet because of racist property laws and contracts, the ownership of the land is in question. As Rayne begins to tackle this issue, he is contacted by his mother, Jewell, who abandoned him to Selma’s care decades ago. Rayne also faces a decisive point in his relationship with his girlfriend, whose son has just begun to call him “Dad.” That’s four generations right there—or five, if you count the one skipped between Jewell and Selma—and the author will add cousins, aunts, uncles, stepfathers, and more to the troop.

At first, Rayne isn’t particularly interested in digging up his family’s history, but inevitably, in confronting the land issues, he must uncover a good deal more than he ever wanted to know. Having tried my own hand at stories that dredge up the past, I was intrigued with the tone of this book, which strikes me as an interesting mix.

From the start, we know from all the elements that form a tone—the style, the positive resolution of small incidents, the degree of humor and warmth, the preponderance of good people, etc.—that nothing really terrible will happen to the main characters in the present-day story. I refuse to label that comment with a “spoiler alert” because the comfortable tone is evident from the first chapter. Yes, Selma is extremely old and doddering, and Jewell’s husband is sick with cancer. Perhaps one or both of these fine folks will die in the course of the novel—I won’t reveal that; see, I’m being good!—but, even so, that will not make a tragedy. We know that Rayne and Jewell will survive and most likely continue the relationship they have newly established.

The past is another matter. When Rayne descends into the dark cellar of this family’s history, he unearths not skeletons so much as bloody remains—the still-dripping evidence of racial violence. No humor and warmth there, just ugliness and calamity, and the author presents them in gory detail:

He raises the tire iron in his hand and the others stand clear of him, because he is swinging wild, hitting the hood, the car door, hitting [the victim’s] legs, shattering the windows, and grabbing through the window at the great, flailing, dangerous, bloodied body.… [He] cuts up his own arm. It bleeds onto the car door and down his side. He lets out war yells like an Indian.

What’s the effect of such a tragic, violent tale wrapped inside a warm and slightly sentimental one? Though I was interested in the gradual revelations of the past, I can’t say I felt suspense, because the outcome—the contemporary lives of the main characters—is already known. In fact, though the villains of the past have present-day descendants, with whom Rayne has to deal to resolve the land issue, Cary treats that story line summarily. Ultimately the past becomes a vivid, personalized history lesson more than a tension-filled story.

The lack of suspense hardly matters, however. Throughout, the characters are the strength of this work. They are big, passionate people struggling to do the right thing. Bringing the scattered relatives back together and understanding what happened to drive them apart—these are the keys to the family’s redemption, and that theme is what Cary wants us to take away from the novel. I’m taking it, and I won’t soon forget Rayne and Jewell and Selma. Another good read from Lorene Cary.

The Literary Hibiscus: A Complaint About Symbolism

February 19, 2011

Back from the near-dead. Seventy-hour work weeks, snow, freezing temperatures, lack of sun, topped off by a virulent head-and-chest virus that apparently laid waste to Baltimore before attacking Philadelphia—all have made this a miserable winter. Granted, we’re sissies here in the mid-Atlantic, and I admit that I could never live in Minnesota, even if Garrison Keillor dropped by nightly to tell stories. Still, I enjoyed pitying myself, and if this is the only happiness one gets for months at a time, that qualifies as misery, doesn’t it?

In these lost months I’ve managed to read just one book, Chimamanda Adichie’s first novel, Purple Hibiscus. I haven’t yet tried her second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, or her story collection, The Thing Around Your Neck.

Purple Hibiscus, as the reviewers said, is a classy debut. Though the background is the Nigerian political scene, the focus is on a single family with a domineering father, passive mother, and two children trying to cope with the impossible situation created by the parents—something that should hit home for me, since I’ve written an American novel with the same setup. And I did respond acutely, enjoying even the long stretches when it seems the teenage narrator-protagonist, Kambili, will never get up the gumption to strike out for freedom from the oppressor. Adichie gives her characters enough complexity to challenge our simple presumptions: the abusive father has many good points, and the more attractive characters, while never verging on evil, have quirks to keep us interested.

She’s good at description, offering simple but vivid detail about daily life:

Obiora was pounding a yellow mango against the living room wall. He would do that until the inside became a soft pulp. Then he would bite a tiny hole in one end of the fruit and suck it until the seed wobbled alone inside the skin, like a person in oversize clothing. Amaka and Aunty Ifeoma were eating mangoes too, but with knives, slicing the firm orange flesh off the seed.

And a moment later, when flying termites course past the apartment complex:

The air was filling with flapping, water-colored wings. Children ran out of the flats with folded newspapers and empty Bournvita tins. They hit the flying aku down with the newspapers and then bent to pick them up and put them in the tins. Some children simply ran around, swiping at the aku just for the sake of it. Others squatted down to watch the ones that had lost wings crawl on the ground, to follow them as they held on to one another and moved like a black string, a mobile necklace.

It helps that the scenes are exotic to Western readers. We can read a sentence like

Lunch was jollof rice, fist-sized chunks of azu fried until the bones were crisp, and ngwo-ngwo.

with a fascinated hunger that we might not feel if the ingredients were more familiar:

Lunch was baked beans, fist-sized chunks of breaded chicken deep-fried until crisp, and cole slaw.

Still, the power of description is in the vivid, accurate details, and Adichie gets those right—as far as this Western reader can tell. (The azu does sound good, whatever it is. Wikipedia says it’s a Japanese R&B singer.)

The one crispy bone I have to pick with Adichie concerns the purple hibiscus, the title flower. In the novel’s extended family, Aunty Ifeoma, the liberal, liberating force, happens to grow an unusual purple hibiscus that her neighbors all admire. The narrator’s brother, Jaja, takes some of Ifeoma’s purple flowers to plant in the garden by his own house, and soon afterward he plucks up the courage to defy his father. At the end of the first section, the narrator makes sure we see the connection: “Jaja’s defiance seemed to me now like Aunty Ifeoma’s experimental purple hibiscus: rare, fragrant with the undertones of freedom. … A freedom to be, to do.”

I’m on a bit of a crusade against standard literary devices, which seem to me all too pervasive in contemporary writing, and this kind of heavy-handed symbolism, which I suspect Adichie absorbed from evil Western influences, ticks me off. The innocent hibiscus plant itself plays little role in the novel; it’s there just to be loaded down with symbolism. Let it go free, I say, free from the burden of representing freedom! Liberate it from the novelist’s manipulation. And don’t make those flying termites into symbols either. If you build the meaning into the action, the characters, the setting—as Adichie has done so admirably—we readers don’t need symbols as a side dish with our crispy azu.

Of Zweig and Patience

October 18, 2010

A year or two ago my wife and I discovered Stefan Zweig (1881–1942), an Austrian writer whose memoir The World of Yesterday paints a lively picture of Europe before, during, and after World War I. Zweig knew every poet, novelist, dramatist, and artist on the scene; a devoted pan-Europeanist, he translated dozens of his friends’ works and wrote biographies of cultural figures ranging from Erasmus to Nietzsche to Balzac. In 1942, shortly after he finished the memoir, in exile in Brazil and despairing as Europe dove deep into another round of self-butchery, he and his wife took their own lives.

In the memoir’s last chapters, he speaks of the disbelief and agony that he and others like him experienced as they witnessed Hitler’s rise. On a Sunday morning he hears the radio news of the declaration of war, “a message which meant death for thousands of those who had silently listened to it, sorrow and unhappiness, desperation and threat for every one of us.”

After reading the memoir, we were moved enough to explore his other work. Despite his vast output of nonfiction and drama, Zweig found time for a number of novels, stories, and novellas—intense psychological works that examine the characters’ thoughts and emotions in exquisite, sometimes excruciating, detail. His writing is marvelous, his characters strange enough to feel very contemporary. And yet I have the typical problem of our A.D.D. age: attention span.

Look at the following passage from The Post-Office Girl (trans. Joel Rotenberg, New York Review Books, 2008). The title character, Christine, a penurious young woman from a small town, has been invited by a rich aunt to visit a magnificent resort in the Alps. When her aunt tells her to “freshen up” before lunch, Christine is amazed, bewildered, awed, and humbled by the luxurious hotel room she is given. We join the action, if it can be called that, about halfway through a two-page paragraph:

Discovery upon discovery: the washbasin, white and shiny as a seashell with nickel-plated fixtures, the armchairs, soft and deep and so enveloping that it takes an effort to get up again, the polished hardwood of the furniture, harmonizing with the spring-green wallpaper, and here on the table to welcome her a vibrant variegated carnation in a long-stem vase, like a colorful salute from a crystal trumpet. How unbelievably, wonderfully grand! She has a heady feeling as she imagines having all this to look at and to use, imagines making it her own for a day, eight days, fourteen days, and with timid infatuation she sidles up to the unfamiliar things, curiously tries out each feature one after another, absorbed in these delights, until suddenly she rears back as though she’s stepped on a snake, almost losing her footing. For unthinkingly she’s opened the massive armoire against the wall—and what she sees through the partly open inner door, in an unexpected full-length mirror, is a life-sized image like a red-tongued jack-in-the-box, and (she gives a start) it’s her, horribly real, the only thing out of place in this entire elegantly coordinated room. The abrupt sight of the bulky, garish yellow travel coat, the straw hat bent out of shape above the stricken face, is like a blow, and she feels her knees sag. “Interloper, begone! Don’t pollute this place. Go back where you belong,” the mirror seems to bark. Really, she thinks in consternation, how can I have the nerve to stay in a room like this, in this world! What an embarrassment for my aunt! I shouldn’t wear anything fancy, she said! As though I could do anything else! No, I’m not going down, I’d rather stay here. I’d rather go back. Bur how can I hide, how can I disappear quickly before anyone sees me and takes offense? She’s backed as far as possible away from the mirror, onto the balcony. She stares down, her hand on the railing. One heave and it would be over.

This scene goes on for another long paragraph in which Christine frets over what to wear, worries what the maid will think, and finally “scurries down the stairs with downcast eyes.”

I admire this writing tremendously—“timid infatuation,” a carnation like a trumpet’s salute—but at some point in the piling of detail upon detail, I become impatient. “I get the point!” my inner voice yells at the author; “let’s move on, OK?”

Then I remember what Stanley Fish once said to a seminar of undergraduates. The more the culture emphasized reading fast, he declared, the slower he read. He engaged us in examining Milton line by line, word by word, almost syllable by syllable.

I try to keep that perspective in mind. No, I lecture myself, don’t read Stefan Zweig while you’re simultaneously watching baseball, checking e-mail, and snacking on the delicious nut-cranberry mix from Trader Joe’s. Both hands on the book, please. Both eyes on the text. Slowly, patiently. Writers as good as Zweig deserve this much from us, and more.

Fishing for Readers: The Apostles Creed of Literature

October 15, 2010

“The two young men—they were of the English public official class—sat in the perfectly appointed railway carriage.”

We hear so much about the need for a “hook,” something to grab the reader immediately, that I take more and more pleasure in authors who ignore that dictum, or who wrote before it became the Apostles Creed of Literature.

The sentence quoted above opens Some Do Not…, the first novel in Ford Madox Ford’s magnificent trilogy Parade’s End. Does anything, other than the balance and rhythm of the style, hook us? What are the men doing? Merely sitting. Who are they? Members of a humdrum group of bureaucrats. Where are they? In a railway car whose principal attribute is that it has no faults. This is an anti-hook.

As those who’ve read the trilogy will remember, Ford’s purpose here is to establish the stasis of pre–World War I English society—a stability that will soon be rudely interrupted. Hence the men are seen first as unmoving stereotypes. But even after establishing their stillness, Ford is in no hurry to bring us action. Not until deep in Chapter IV do we reach the scene when Valentine Wannop alters Christopher Tietjens’ life forever by barging up to him on a golf course to demand that he save her friend and fellow suffragette from being manhandled. In the meantime, Ford treats us to, among other things, a description of Tietjens’ companion Macmaster, including his origins, current position, aspirations, and the thesis of the new book whose proofs he has been correcting on the train; a brief history of Tietjens’ disastrous marriage, which leads to an explanation of why the two friends have embarked on a golf outing; a mention of Tietjens’ pastime of finding errors in the Encyclopaedia Britannica; a philosophical discussion of monogamy; a long chapter with the wife, her mother, and a priest, who utters such observations as “’It’s a good maxim that if you swat flies enough some of them stick to the wall”; and, immediately after the opening quoted above, a leisurely survey of that boring railway carriage:

“The leather straps to the windows were of virgin newness; the mirrors beneath the new luggage racks immaculate as if they had reflected very little; the bulging upholstery in its luxuriant, regulated curves was scarlet and yellow in an intricate, minute dragon pattern, the design of a geometrician in Cologne. The compartment smelt faintly, hygienically of admirable varnish; the train ran as smoothly—Tietjens remembered thinking—as British gilt-edged securities. It travelled fast; yet had it swayed or jolted over the rail joints, except at the curve before Tonbridge or over the points at Ashford where these eccentricities are expected and allowed for, Macmaster, Tietjens felt certain, would have written to the company. Perhaps he would even have written to The Times.”

The writing is confoundedly leisurely, as Tietjens himself might have said. It’s also brilliant, pointed, and amusing.

No hooks. The reader isn’t treated as a fish. I admire that, and envy Ford for living in a time when it was possible.

I first read Ford when I was quite young, and now I’m wondering if my convictions about him would change during a new read. By accident in browsing, I discovered one person who has recently come to Parade’s End for the first time and finds it fascinating: see the entry in Hannah Stoneham’s Book Blog, http://hannahstoneham.blogspot.com/2010/04/read-along-of-ford-madox-fords-parades.html.